by Charlie Warmington

My bug for travelling and exploring first bit me on a family expedition to Killybegs in 1953.

The highlight - in every sense - was the lighthouse, topped with huge, incomprehensible, metal mechanisms encircled by thick glass, high above the surf-washed stone jetty where we’d been welcomed by a sturdy lighthouse keeper in waist-high welly-boots.

I was previously acquainted only with wellies - children’s size!

Everything else was completely unfamiliar; the boat’s bilge-water gurgling to the rhythm of rolling waves; the forest of seaweed swaying eerily underneath; the wake frothed white by a salty Atlantic wind.

The trip is as firmly embedded in my memory as the lighthouse’s granite stones in the tower, chiselled in the 1830s.

My fortnightly series of travel and exploration stories begins - 60 years after Killybegs - at a lighthouse!

Lewis and Harris together make up the largest island in Scotland’s Outer Hebrides.

The picturesque archipelago is an ever-changing fusion of heart-achingly beautiful terrains; mountains, hills, rugged coastlines and lunar-like rocky plateaus.

They’re the oldest rocks in Britain and amongst the oldest on earth, punctuated with meadows, moorlands and white, sandy beaches.

On the tip of a remote peninsula on the Isle of Scalpay, the Eilean Glas Lighthouse has safe-guarded shipping in the turbulent sea-lane since 1789.

The world-renowned Harris Tweed factory and the new Harris Whisky (without Ireland’s ‘e’!) Distillery will adorn this page presently, but today is predominantly Eilean Glas.

A bracing blast of Western Isles wind, as if just in from Iceland, blows an invigorating ‘Fàilte gu Steòrnabhagh’ in my ear as I step down a Stornoway Airport disembarking ramp after a one-hour flight from Glasgow.

“People don’t come here for the weather,” says guide Chris Ryan, “if it’s sunny, that’s a bonus!”

He points to “the White House” - not the result of a wrong turn high over The Minch “but that’s what local people call the Isle of Lewis’s local government headquarters,” Chris smiles.

There’s a long stone wall bordering a forest of lofty trees and shadowy glades.

“It’s the only extensive area of broad-leaved woodland on the island,” says Chris.

There are no trees proffering shade when the sun uncharacteristically splits the eagle-patrolled skies above the meandering, two-kilometre moorland path to Eilean Glas.

“This is where the magic happens,” Harris Whisky Distillery’s boss said earlier when he showed me his gleaming stills back in Tarbert.

Magic happens here too as I tramp towards the distant, red and white-banded lighthouse.

The path climbs, plunges and corkscrews between moss-edged moorland lakes, terminating abruptly at a centuries-old dry-stone wall - the lighthouse’s outer boundary that encloses other smaller buildings and out-houses precariously clutching the cliff.

“They kept sheep,” Chris explains.

Below is a picture-postcard harbour “for unloading provisions for the lighthouse men’s families” adds Chris.

A stone-walled garden supplemented deliveries with fresh vegetables that were vital when storms cancelled the lighthouse folk’s orders.

Some hardy ancestral daffodils have long-outlived the vegetables.

Eilean Glas, named after Glas Island, was one Scotland’s first four lighthouses.

Its original tower, completed in 1789, was four feet wider than planned, but what the heck - stonemasons George Shiells and John Purdie were only paid a few pennies a day!

In April 1789 the wonderfully named ‘Kelly and Nelly’, a boat from Wick, delivered the lighting equipment.

Alex Reid, a sailor from Fraserburgh, Eilean Glas’s first keeper, was picked up with his family on the way.

When Reid was pensioned off in 1823 with an annuity of 40 guineas his employers noted that he was “weather-beaten and stiff from long exposure”.

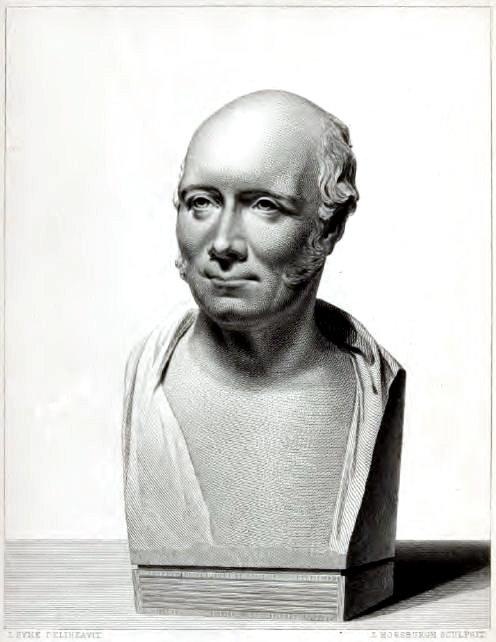

The present light-room, 43 metres above the sea, was erected in 1824 by Scotland’s ‘father-of-all-lighthouses’ Robert Stevenson.

For over 150 years Robert and his descendants, including three sons, designed and built most of Scotland’s lighthouses.

The five bulging air-tanks, pipes and pumps powering Eilean Glas’s cavernous ‘masters voice’ fog-horn were installed in 1907.

When required, it blew seven deafening one-second blasts every 1½ minutes and was eventually disconnected (with an ASBO?) in 1987.

Robert Stevenson’s talented family-tree also sprouted the famous author Robert Louis Stevenson.

It’s thought that his visits to remote, family-built lighthouses inspired Kidnapped and Treasure Island.

“There is scarce a deep-sea light from the Isle of Man to North Berwick,” wrote Robert Louis, “but one of my blood designed it. The Bell Rock stands monument for my Grandfather; the Skerry Vhor for my Uncle Alan, and when the lights come out along the shores of Scotland I am proud to think that they burn more brightly for the genius of my father.”

Full information about Scotland holidays is at www.visitscotland.com and in a fortnight my recent visit to Málaga in southern Spain begins, coincidentally, with another historic lighthouse!

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article