Judging by some of the comments I received, I must have touched a nerve when I wrote recently about children leaving home to go to university; parents have felt the same rollercoaster of emotion as me, a mixture of worry and excitement.

READ ALSO: Denzil McDaniel's The baby eagle only soars when it is pushed out of the nest

Yet these “kids” are adults at 18, and with today’s technology we have Skype or Facetime among many ways of keeping in touch.

Imagine instead back in the early 1960s, packing a 15-year-old son on the ferry to go over to England and fend for himself in a new uncertain career in an unfamiliar city; with a letter a week if you’re lucky to hear how they are.

So began the journey of a slender, shy boy from the Cregagh estate in Belfast. This was how it all started for the young George Best, with only his friend Eric McMordie for company as they headed to Manchester United as young hopefuls. It would be 44 years before the journey was completed for good when Best was buried in his native city; unlike the loneliness of the first journey, George Best was laid to rest a national hero, with a quarter of a million people lining the streets.

Thanks to all who came to see our film tonight.

— George Best Film (@GeorgeBestFilm) October 14, 2016

The First. The Last. The Best. #allbyhimself pic.twitter.com/cA0HOj6c0q

It’s a remarkable contrast, captured in a new film. “George Best: All By Myself” tells the story of the transformation of a sweet 15-year-old, a “good boy”, who became a world icon whose tragedy saw him reduced to an alcoholic, dead at 59 years of age.

At the premiere of the film at Leicester Square in London last week, Tricia Tuttle from the London Film Festival introduced a Question and Answer session with the opinion that George Best “didn’t fulfil his potential”. A glib line which only goes to underscore the misunderstanding of the Best legend, which this excellent film explores.

READ ALSO: Denzil McDaaniel's column on mental health well-being

In the mid-60s, Best was for a few years the best player in the world; in an era of Charlton and Beckenbauer, and when Pele was still at the height of his powers. The Belfast boy was a key figure in bringing the European Cup to England for the first time, and was European Footballer of the Year. In a recent television interview, Bobby Charlton recalled the buzz at Old Trafford when, he said, thousands turned up every week just to make sure they were there when George Best turned on the magic. Which was quite often.

I felt nostalgic watching old footage of the day at Windsor Park in 1967, when Best tortured Scotland full-backs Tommy Gemmell and Eddie McCreadie, who was said to have “twisted blood” after the roasting. I was a young boy in the crowd of over 50,000 that day.

OK, the glittering stardust could have lasted longer; but the fact that 50 years later we’re watching movies about him tells you all you need to know.

While the glory of his exploits on the pitch underpin the film, this is much, much more than a football story. It is a life story, which poses questions about how celebrities cope with our intrusive adulation. It raises sport’s, and indeed society’s relationship with alcohol and a drinking culture, and the media’s treatment of its subjects in this context. And, indeed, the responsibility that individuals themselves have in being sucked into a vortex of problems.

Best often masked his problems; but was he a victim of circumstance, or is the responsibility his own, even wasting the gift of a new liver?

Above all, though, is the human element of Best’s story. I was fortunate to attend the opening night; in the seat in front of me was George’s second wife, Alex, who was emotional and tearful as her great love’s life unfolded on the huge screen. Not least when much of the story was narrated by Best himself, almost a voice from beyond the grave.

The film makers had secured many hours of interviews that George did over the years, and used the audio to dramatic effect, with Best talking about aspects of his life being shown on screen. This included his regret at not doing more for his family, especially after his own mother died after becoming an alcoholic.

One also got a sense from Best’s own lips of how the classic alcoholic denial often kicked in.

There are other voices in the film. There were many women in Best’s life, but only a few of significance. A serious girlfriend for a time in the 60s Jackie Glass, who is now a Buddhist nun living in Edinburgh, speaks about the early days.

His first wife, Angie’s stories about him, particularly in the United States give real insight into the way George descended into addiction; particularly in her dramatic account of driving her child to the doctor one day.

“I see this man walking down the centre of the road. This poor man is all soaking wet, hunched over and I think: ‘Oh my God, that poor, homeless tramp. Then I realise, it’s my husband, drunk as a skunk, staggering home. I just keep driving.”

And Alex, his second wife is featured, with the shocking photos of her bruised face when they had a drink-fuelled fight. In fact, the film is a tough watch, particularly when we learn that at times Best was not the nice individual we always want to think, not always the “good guy taken over by demons.”

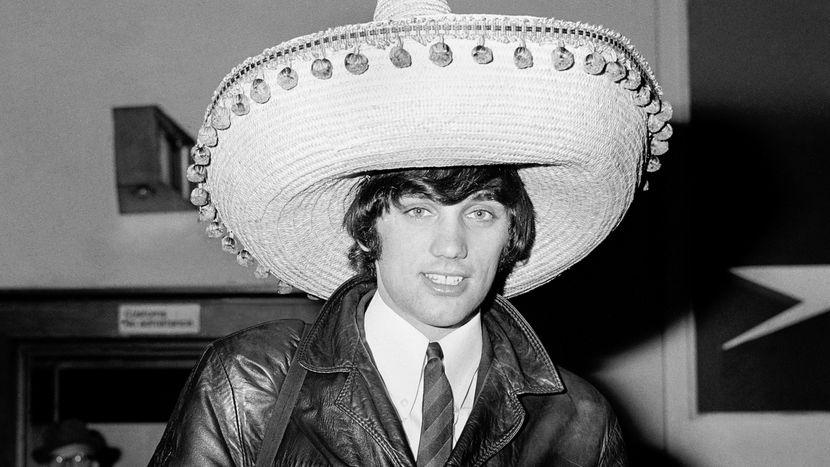

The great Harry Gregg talks about the time in 1966 when Best shot to world prominence with two goals against the magnificent Benfica and, for a laugh wore a big Sombrero on the return flight. Something changed that day, says Gregg perceptively, and at just 20 Best became a world superstar.

The notion is true that Best was the first to be targetted by press intrusion, and that Alex Ferguson once told him that he uses his example to warn young players about the dangers of excess.

But if we have a system of throwing bucket loads of cash at footballers, young men with more money than sense are still falling into traps, as stories of drink, gambling and sex fill the tabloids most weeks. And look at Gazza and his addiction. Are the media ruining him, or is he ruining himself? Like him, we ask if enough was done for George Best, or was his self-destruct streak so strong that, really, nothing would ever have been enough.

Despite the fact that it doesn’t pull any punches, the joy that Best brought is still at the heart of this film.

Best himself tells us, prophetically, in a clip that when he’s gone he wants to be remembered “for the football” and that all the other “crap” will be forgotten.

I still want to think of him that day at Windsor in 1967; or in the Benfica game of 1966 when commentator Ken Wolstenholme’s dulcet tones announced: “It’s Best again, what a player this boy is.”

But, in the film, it’s left to the doyen of journalists, the gravel-voiced Hugh McIlvanney to remind us that George, (indeed any of us) doesn’t get to make the choice of how we’re remembered.

This film examines all the aspects of an extraordinary life.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here