Next month marks the Centenary of the end WWI, also known as the Great War or ‘the War to End all Wars’.

Publics events of all sorts are being held here, and around the UK and the world, prior to the main memorial events on 11 November.

On that day Enniskillen and Fermanagh will remember the sacrifice of millions of men and women by joining in the National Commemoration, a global event collectively called ‘the Battle's Over - A Nation's Tribute’.

The Impartial Reporter is marking the Centenary with regular commemorative articles.

Captured ‘trophy guns’ brought here from the fronts lines have already been recounted, as well as the ‘hospital trains’ that brought home wounded troops.

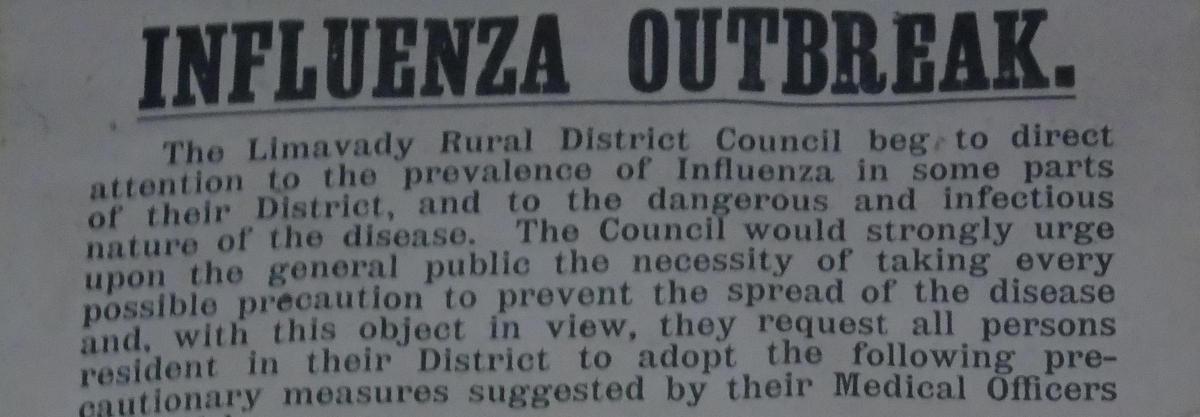

Over the next weeks there’ll be archived narratives from front-line soldiers themselves, details of the horrendous flu virus they carried home which brought death to many thousands of civilians across Ireland, and other local war-related accounts.

Today’s focus is on the context and impact of the Great War.

The Irish Home Rule issue was to the fore when war began. The border wasn’t yet on the maps and substantial numbers of Irish folk lived and worked far beyond Ireland’s shores, factors which ‘muddle’ the archived data.

One thing is indisputable - WWI’s overall statistics were unimagined and unimaginable - a total of around ten million military deaths, over 21 million military wounded, almost eight million missing or taken prisoner and nearly nine million civilian casualties.

War began, after several months’ build-up, on Monday 4 August 1914.

At 11 pm British-time and midnight German-time the two countries commenced hostilities and war ‘formally’ started.

The Armistice was signed on 11 November 1918, and a precise analysis of the tragic Irish-related statistics that burgeoned hideously between those dates is difficult to define for a number of reasons, such as an Irish soldier’s actual place of birth (i.e. Irishmen born abroad), their stated nationality on the ‘signing-up’ documents, and anyway, many records are unreliable or confusing, or both!

So detailed figures vary, but from August 4, 1914 to November 1918 it’s generally agreed that more than 200,000 Irish people served, including over 60,000 from the north.

Around 40,000 Irishmen died, about 10,000 of those from what is now Northern Ireland.

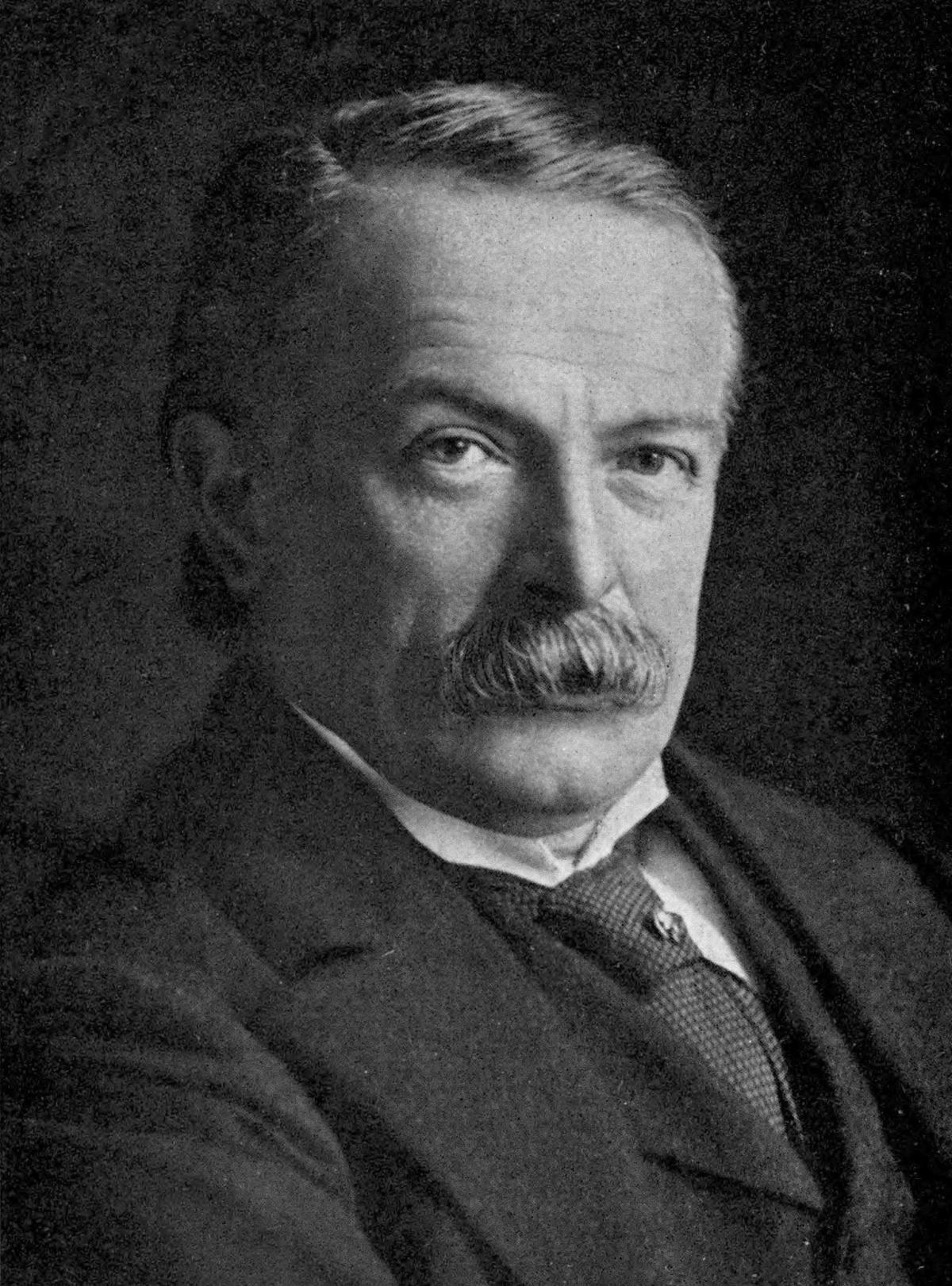

The late, highly-acclaimed, Professor Keith Jeffery, Professor of British History at QUB, compiled three main categories of Irishmen who volunteered.

The first category was made up of the men who were already in the British army - 28,000 Irish-born regular soldiers and 30,000 reservists.

Secondly, there were ‘Kitchener’s men’ who responded to the iconic ‘Your Country Needs You’ posters.

Lord Kitchener’s urgent beckoning between August 1914 and February 1916 enthused about 95,000 Irishmen to join up.

Professor Jeffrey’s third category was “those who joined up during the rest of the war, after the initial recruiting ‘surge’, up to November 1918.”

He put this figure at about 45,000, including nearly 10,000 recruits in the last three and a half months of the war alone.

Numbers not available for inclusion were officers from Ireland, Irishmen in the Royal Navy or in armies outside the United Kingdom such as Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and the USA.

Amongst the numerous WWI plaques and memorials all across Fermanagh and the surrounding region, Enniskillen’s War Memorial bears the names of 581 local men and one woman who died.

Some were teenagers, others nearing their sixties, but most were in their twenties and thirties - Roman Catholics and Protestants; fathers and sons; two siblings and sometimes three from the same family.

Around 200 names aren’t on the Memorial and when it was built almost 1,000 disabled and injured local men were receiving war pensions.

“March no more my soldier laddie,

There is peace where there once was war.

Sleep in peace my soldier laddie,

Sleep in peace, now the battle’s over.”

Those moving words were put to ‘When The Battle's O’er’ - a late 19th Century retreat played by bagpipers calling soldiers to a roll-call after action.

All too often names on the roll went unanswered.

When The Battle’s O’er will be played here and around the world on the morning of the 100th anniversary of the end of the Great War.

And whilst Enniskillen will be the most westerly town to hear the bagpipers’ retreat next month, Fermanagh-folk were the first to know that war was over - “three hours earlier than Belfast, Derry, Dublin or even London itself” boasted the Impartial Reporter - because a wireless operator in Enniskillen’s military barracks intercepted a Morse code signal from France, where the Armistice was signed.

The joyful news had already spread across Fermanagh before Prime Minister Lloyd George announced it at 10.30 am, a Battle’s O’er that’s being commemorated here a century later, in memory of the local people on WWI’s battlefields, in the sea and air, and on the home front.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here