Sergeant William Robert Brabrooke of the 11th Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers was a member of staff in Enniskillen’s

Co-Op in Henry Street.

He lived with his wife Florence and three children in 15 New Row, Enniskillen.

Sergeant Brabrooke was only 31 when he was buried in Breandrum Cemetery in April 1918.

He was honoured with a full military funeral; he’d fought and was wounded at the Battle of the Somme on 1 July 1916.

After the Somme he wrote a letter to his wife telling her

“we did splendid work.”

“He was one of the coolest, best sergeants in my company,” an officer told Florence after the funeral.

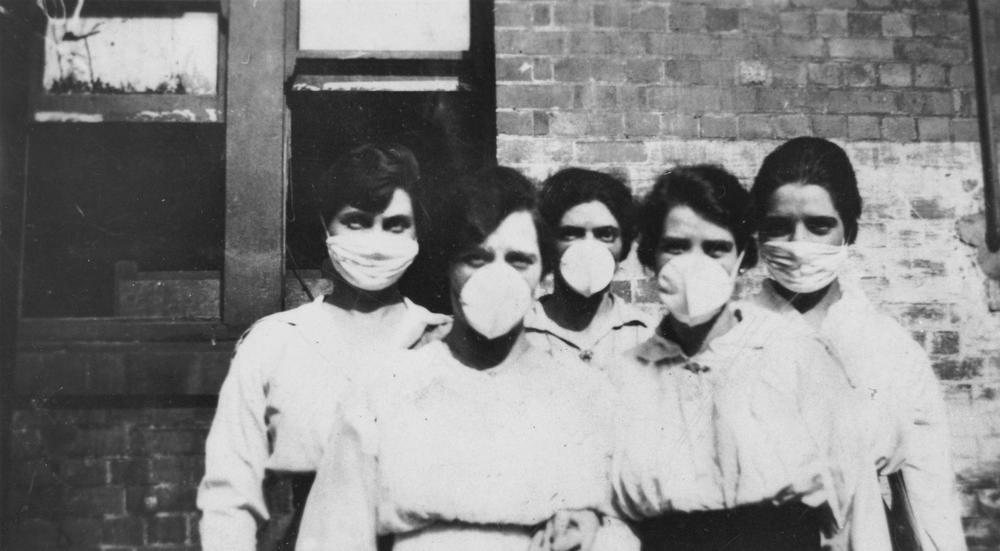

Sergeant Brabrooke fought on in France for almost two years after the Somme, until he was invalided home with influenza which rampaged mercilessly along the front lines towards the end of WWI.

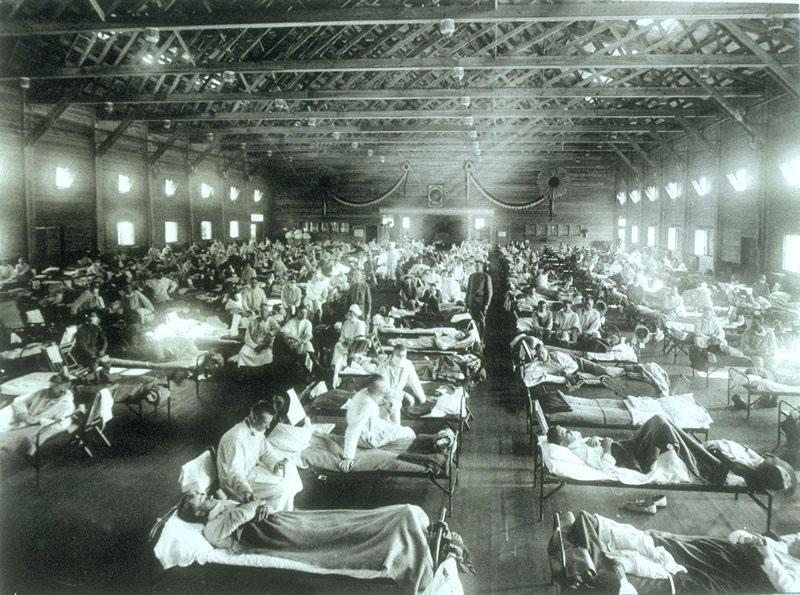

The trenches were fertile ground for the epidemic, with exhausted, malnourished soldiers cramped together in the mud, often with little, if any, protection from the elements.

James Quigley was with the 11th Inniskillings on the Western Front in the winter of 1915.

“We are billeted in a small barn,” he wrote in a letter to his mother “and it’s kind of ‘Pat said turn and we all turned’, as we’re packed like herrings in a barrel, but of course that makes us all warmer at night.”

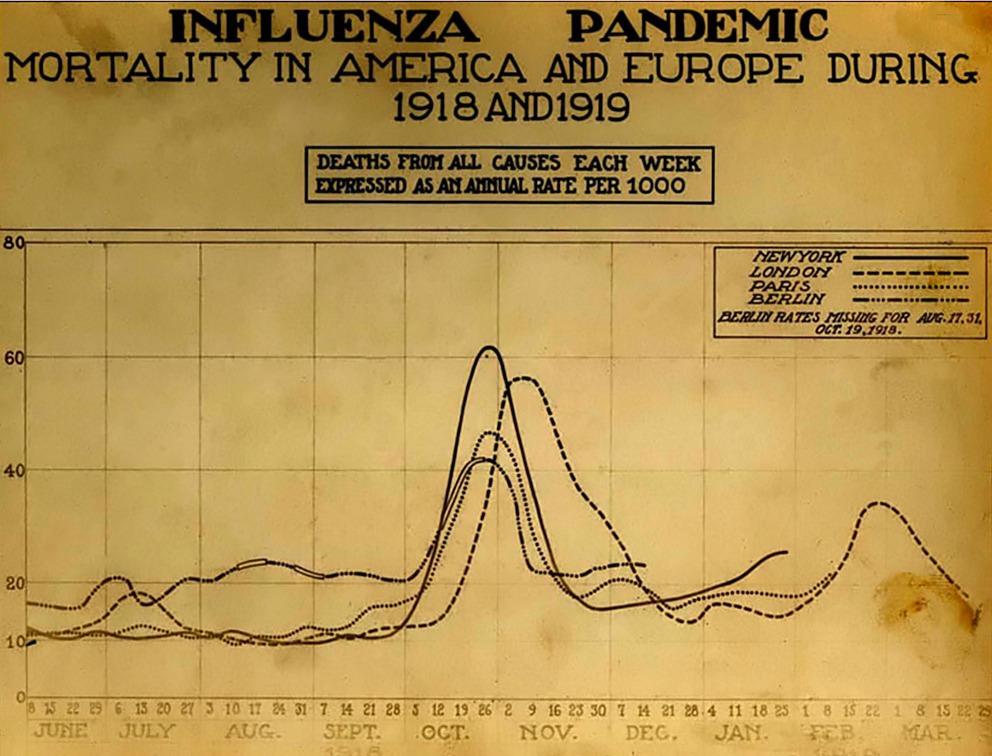

It also nurtured the flu epidemic - nicknamed ‘Spanish Flu’ - which the multi-national troops brought home after the Armistice, infecting up to 500 million people around the world.

Between 50 to 100 million died.

“The influenza epidemic has laid low some districts,” reported the Impartial Reporter in November 1918, adding “in the Fivemiletown district there have been many deaths, as many as two in the one family taking place. Clones town and district has also suffered.”

Sir William J. Thompson MD from Cavanaleck, County Tyrone, and schooled in Enniskillen, was Registrar-General of Ireland from 1909.

“Since the period of the Great Famine with its awful attendant horrors of fever and cholera,” said Sir William in 1919 “no disease of an epidemic nature created so much havoc in any one year in Ireland as Influenza in 1918.”

Sir William concluded that out of the 800,000 people in Ireland who caught the flu the full tally of deaths was probably over 16,000.

“The influenza epidemic left the Enniskillen Workhouse in a state of chaos,” said the Impartial Reporter “corpses lay for three days unburied.”

Around 130 tram workers succumbed to the flu in Dublin where the service virtually ground to a halt.

A dancer died whist performing on a Belfast stage.

Most of Tipperary’s policemen caught it, Limerick’s cinemas closed their doors and a GAA final was postponed.

Sir William J. Thompson’s horrifying statistics were augmented by his conclusion that the spike in pneumonia deaths in 1918 was also caused by flu.

Altogether over 2,000 died in Belfast and over 200 in Londonderry.

Over 500 died in Donegal, over 2,000 in the borough of Dublin, around 250 in Limerick and over 300 in Cork.

Whilst parts of Fermanagh were very badly affected, there were relatively few deaths according to Sir William Thompson - “the six counties having the lowest rates per 100,000 of the population were Clare (46), Mayo (88), Kerry (94), Leitrim (99), Roscommon (107), and Fermanagh (110).”

In Fermanagh 36 males and 32 females died of flu in 1918, making a total of 68.

Another 70 died from pneumonia, which, according to Sir William, was probably because of flu.

“In Clones, too, some places of business have had to close owing to the whole family being prostrated,” the Impartial Reporter stated, “and the police, usually immune from epidemics, have also fallen victim - nine of the Clones force being in bed ill.”

On 19 December 1918 the Impartial Reporter’s account from Enniskillen’s workhouse outlined the state of chaos - “Not only were the Master, Matron and Schoolmistress ill, but Nurse Macklin was also confined to her bed. The workhouse was full of influenza cases, and many patients had to lie on the floor. Three corpses lay for three days unburied.”

All of Enniskillen’s schools were closed due to the epidemic and “our Royal School was badly crippled, owing to the number of cases” said the Impartial “but Major Bruce, Army Medical Corp, very kindly sent nine of his Army nurses to Portora, and this very sight cheered the boys, as they ministered to them.”

The nurses’ devotion evidently paid off according to a later report in the Impartial about the Armistice celebrations - “the Portora boys, the majority of whom had been in bed, are convalescent, and took part in the rejoicings of Monday night last, carrying an effigy of the Kaiser through the town, and afterwards setting fire to it amid much enthusiasm.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here