By The Impartial Explorer

Almost two years ago in April 2017 a gripping story about the Fermanagh-born explorer Andrew Montgomery was recounted on these pages.

Born around 1792, Andrew left Enniskillen and became a surgeon on a convict ship.

He sailed to Australia where he joined the expedition that discovered and mapped the rugged, remote and breathtakingly beautiful Kimberley Coast of Western Australia.

Today the coastline is one of that vast continent’s most popular tourist locations.

The Montgomery Reef, one of the Kimberley Coast’s 3,000 islands, reefs and countless picturesque bays is named after Andrew.

Though parts of the coastline were probably inhabited by indigenous peoples in the distant past, on 23 June 1821 the Enniskillen traveller was the first human being from more modern times to step onto an 80-km-long (50 miles) island.

Little is known of Andrew after his Australian exploits though he lived to tell his intriguing tale to friends and acquaintances.

Not so for a Galway-man who went to Australia 40 years later.

A diary-entry written in 1861 employed a quote from Charles Dickens to describe a tragedy in the still-unexplored country that so enamoured Montgomery.

“Mr Burke suffers greatly from the cold and is getting extremely weak,” wrote William John Wills, adding “I can only look out like Mr. Micawber ‘for something to turn up’.”

(Micawber is the optimistic clerk in Charles Dickens’s 1850 novel David Copperfield.)

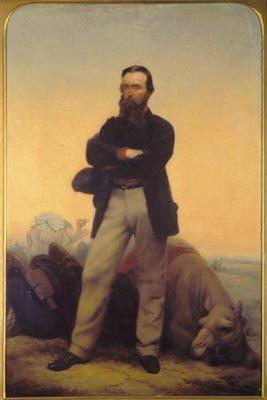

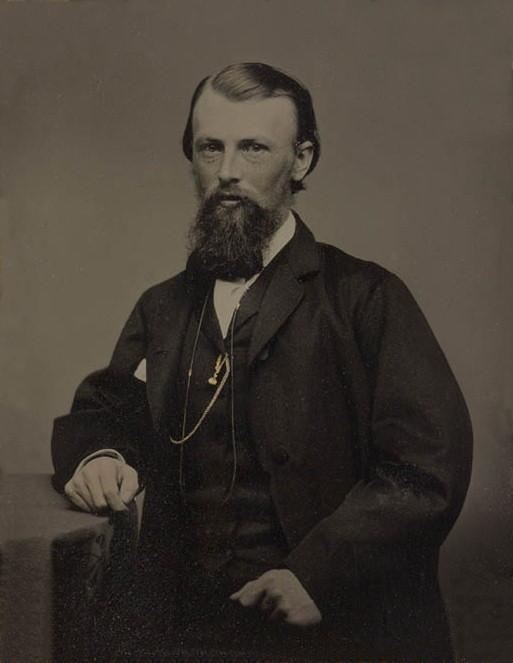

Mr Burke was Galway-man Robert O’Hara Burke, William Wills’ colleague-traveller on the famous ‘Victorian Exploring Expedition’ of 1860/61 in inland Australia.

Also known as the Burke and Wills expedition, it remains as one of the most celebrated journeys of the ‘heroic era’ of Australian land exploration.

Robert Burke was born at St. Cleram, County Galway, in 1820.

William John Wills, born on 5 January 1834, was a British surveyor and surgeon, second-in-command of the ill-fated Burke and Wills expedition.

Burke joined the Irish constabulary in 1848 and in 1853 emigrated to Australia where he became an inspector of police in Victoria.

In 1860 he was appointed to command an exploring expedition despatched for the purpose of crossing the Australian continent from south to north.

Wills’ and Burke’s diaries of the journey describe the impossible odds they faced in the unknown outback and

their tragic fate received international attention.

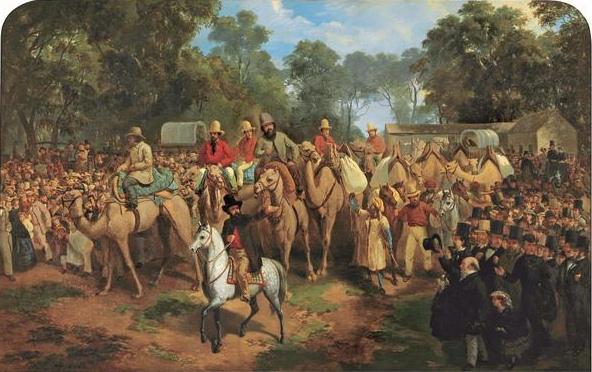

When they started out, it was described as the best equipped expedition in Australia’s history.

Led by the Galway-man, the team of explorers set off with some 21 tons of equipment.

Their departure from Royal Park in Melbourne on 20 August 1860 was a major public event and they were given a rousing farewell by over 15,000 onlookers.

A novel feature was their camels, specially imported from India, from which great results were expected.

Dissensions soon arose, and several members of the exploration team dropped out.

Burke and Wills reached Cooper’s Creek on 11 November, one of three major Queensland river systems that flow into the Lake Eyre basin.

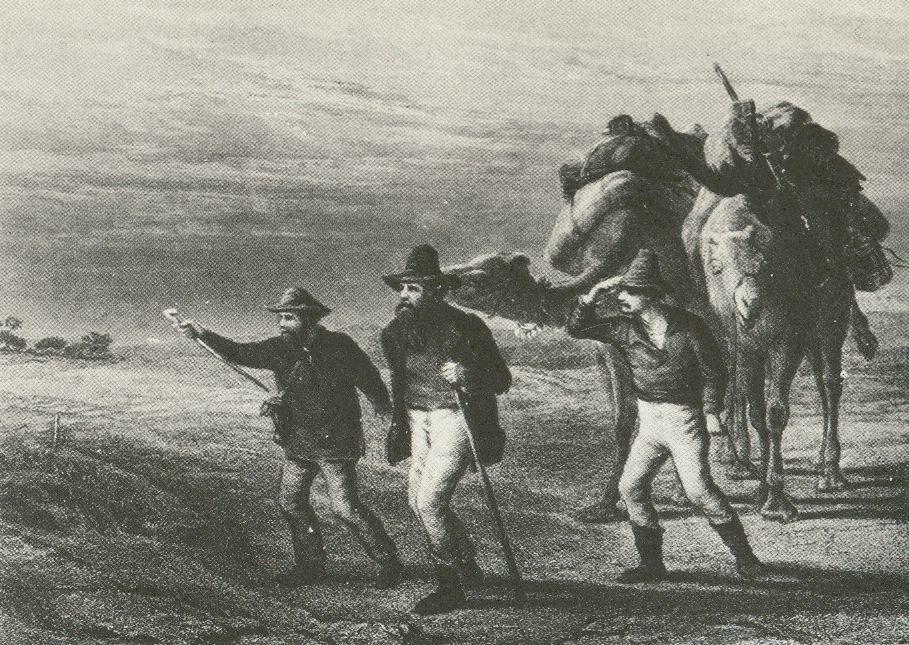

After a long wait for supplies, which failed to arrive, they

made a dash for the Gulf of Carpentaria on 16 December, leaving the bulk of their stores in charge of one of their team members, with directions to await their return in three or four months.

Though not actually coming within sight of the sea at the other end of Australia, Burke and Wills reached the tidal waters of the Flinders River and won the fame of being the first white men to cross the Australian continent.

But on their return to Cooper’s Creek on 21 April 1861, exhausted with hardships, they found that their companion

had interpreted his instructions too literally and abandoned his post that very same day, leaving only a small stock of provisions.

Against the advice of Wills, who wanted to chase after their companion and retrieve their supplies, Burke determined to strike for other stores along the route, which he had been misled into believing were much nearer to Cooper’s Creek than was actually the case.

He was driven back by want of water, and, too weak to make another attempt, was constrained to wait at Cooper’s Creek, subsisting mainly on food casually obtained from friendly natives, themselves scarcely able to subsist in the desert.

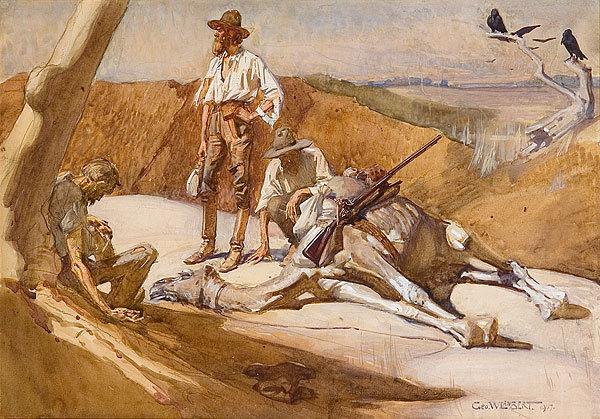

Burke died of starvation on 28 June 1861 and Wills around about the same time.

Only one explorer, John King, survived the return journey.

Near death, he was cared for by the indigenous Yandruwandha people until a relief expedition rescued him.

Amongst the others who died were Charles Gray, Ludwig Becker, Charles Stone, William Purcell and William Patton.

One of the final, weakly-written notes in William Wills’

diary describes a “clear cold night, slight breeze from the east”.

The diary refers to Burke’s extreme weakness due to starvation and tragically concludes “nothing now but the greatest good luck can now save any of us.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here