It’s very appropriate that a large gable-end mural in Larne, County Antrim, is above a shoe shop.

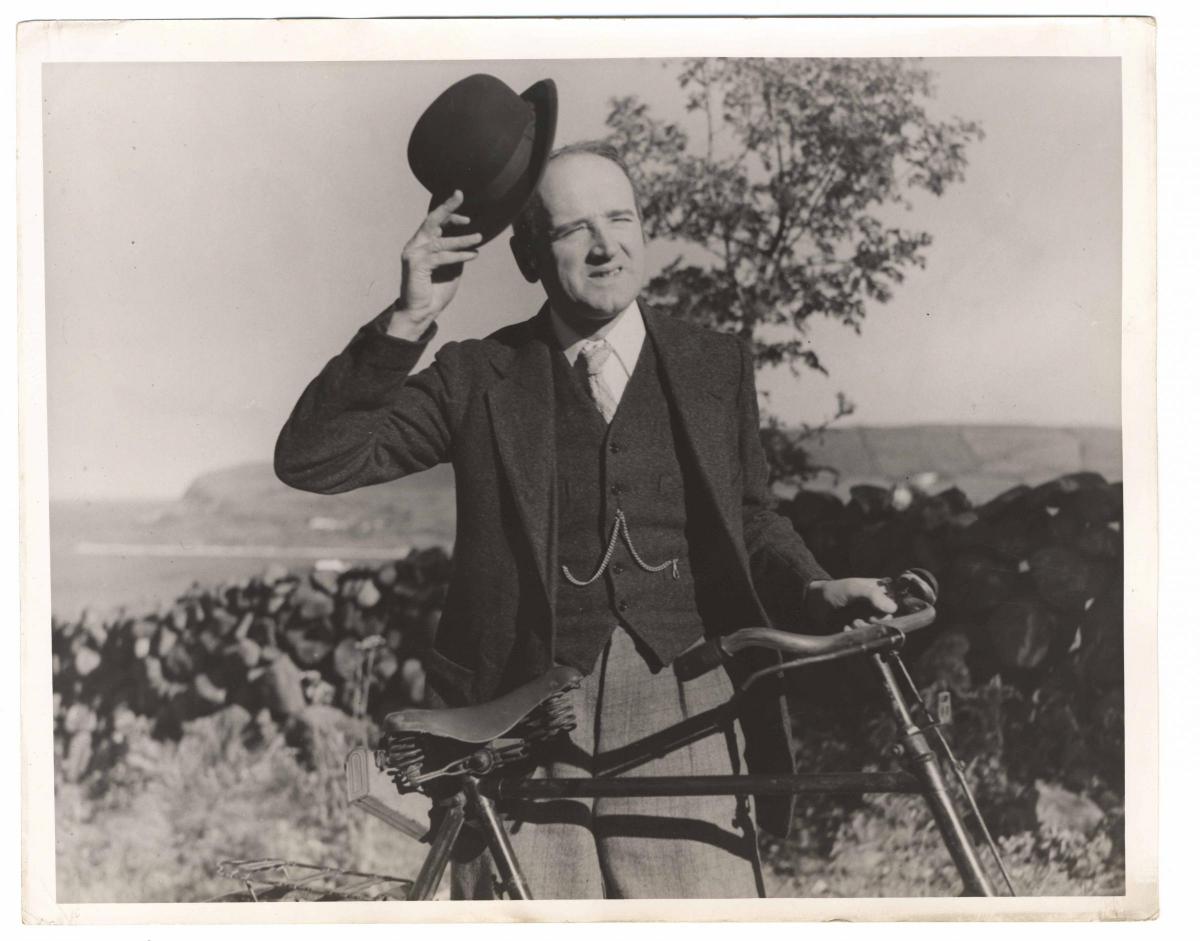

It depicts Lancashire-born Richard Hayward who moved with his family to Larne in 1895 when he was three years old.

Hayward’s characteristic footprints are all over Ireland, both geographically and culturally, and though virtually forgotten until quite recently he was a cultural giant, north and south, during the middle decades of the 20th century.

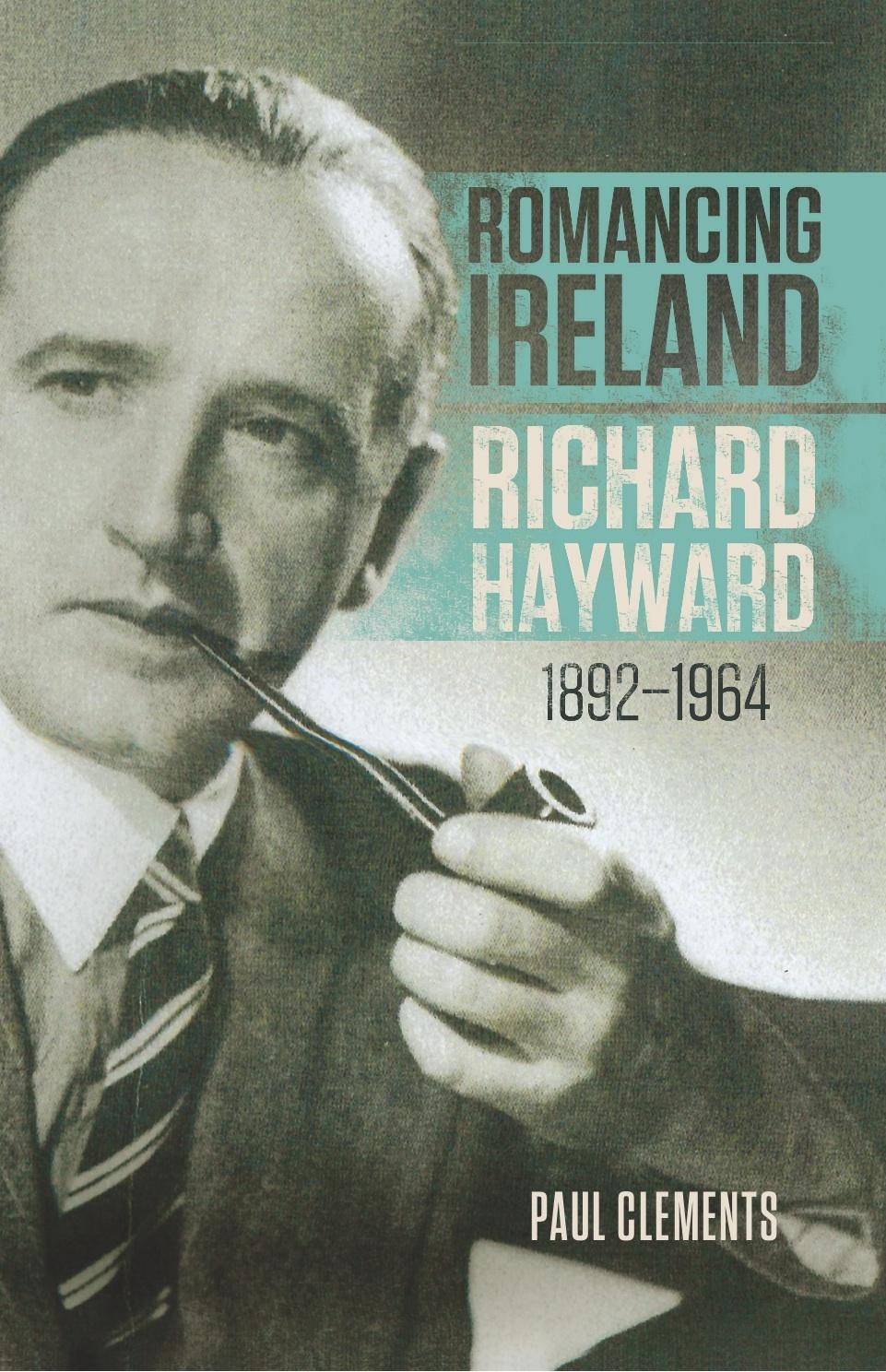

Described as “an early example of the cult of celebrity” by biographer Paul Clements, Hayward’s name and remarkable achievements were at best neglected and at worst ignored since his death in a car crash near Ballymena in 1964.

The sights, sounds and citizens greatly inspired him as he trod the streets of Larne as a youngster, a continuing inspiration as he trod the boards of Ireland’s leading theatres as an adult.

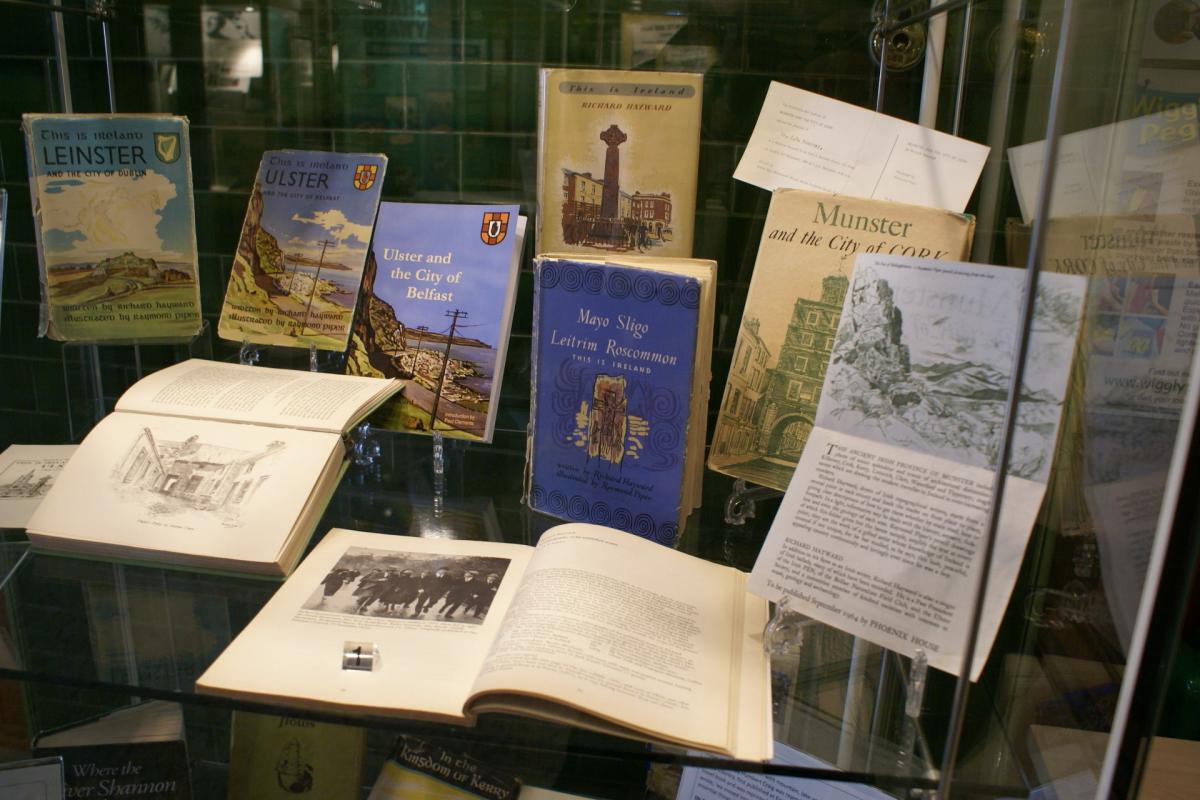

As well as writing 17 books, editing two and contributing to 12 other publications, he authored five music books, composed, arranged or selected numerous tunes and songs for sheet music and recorded over 150 traditional Irish songs and ballads with Decca Records.

Hayward acted in, narrated, directed or contributed to almost 30 feature films, travelogues, documentaries and various marketing and promotional footage.

Over a dozen of the movies he acted in were epic, like A Night to Remember in 1958 and The Quiet Man in 1952.

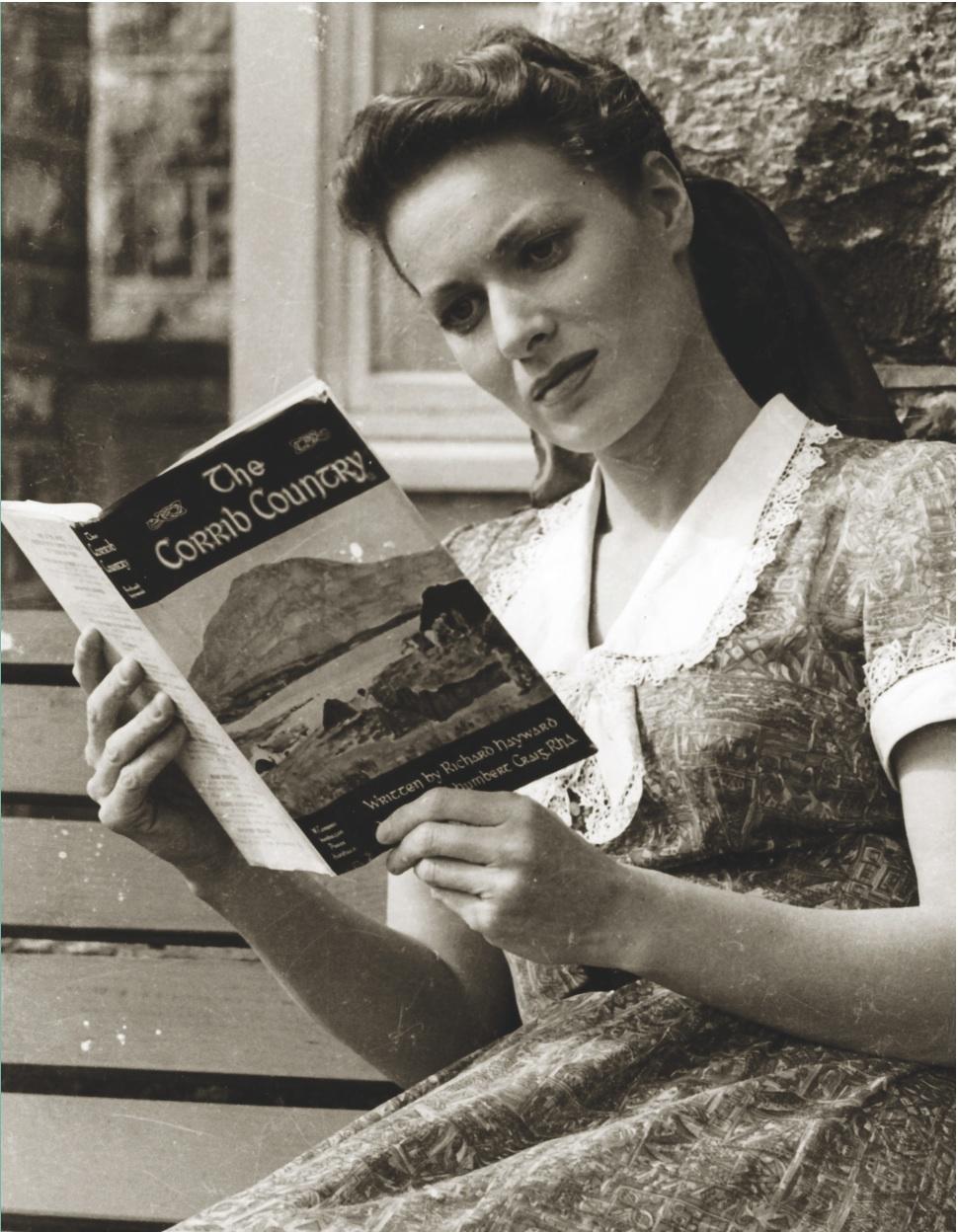

An enduring image from the latter is a photograph of Maureen O’Hara reading Hayward’s book ‘The Corrib Country’ while taking a break from her starring role as Mary Kate Danaher.

Between 1920 and 1937 he acted in over 28 major theatre productions, often as the leading man, and he was showcased in a 1950 concert with Frankie Vaughan, Vera Lynn and Lee Lawrence.

He was also a theatre impresario, archaeologist, humourist and member of a diverse range of clubs and societies.

When he wasn’t writing or performing, Hayward supplemented his family income supplying confectionary shops with mints, toffees, fruit pastilles, chocolate bon bons and buttered Brazils on behalf of Fox’s Glacier Mints and the Needler’s Chocolate company.

Some of his mints were displayed recently at a temporary exhibition about Hayward’s life and work in Larne’s Museum and Arts Centre.

His vast and varied output was vividly evident in the exhibition with shelves of his travel books from every corner of Ireland, his much-used travel trunk and suitcase and even some of his travelling and more formal clothes!

There were artefacts from his school days in Larne Grammar School and from his time as excursion leader and President of the Belfast Naturalist’s Field Club.

He had close associations with the Fermanagh Field Club too, who sent his family a note after his death - “he lit the fields of Ireland with a brilliant light.”

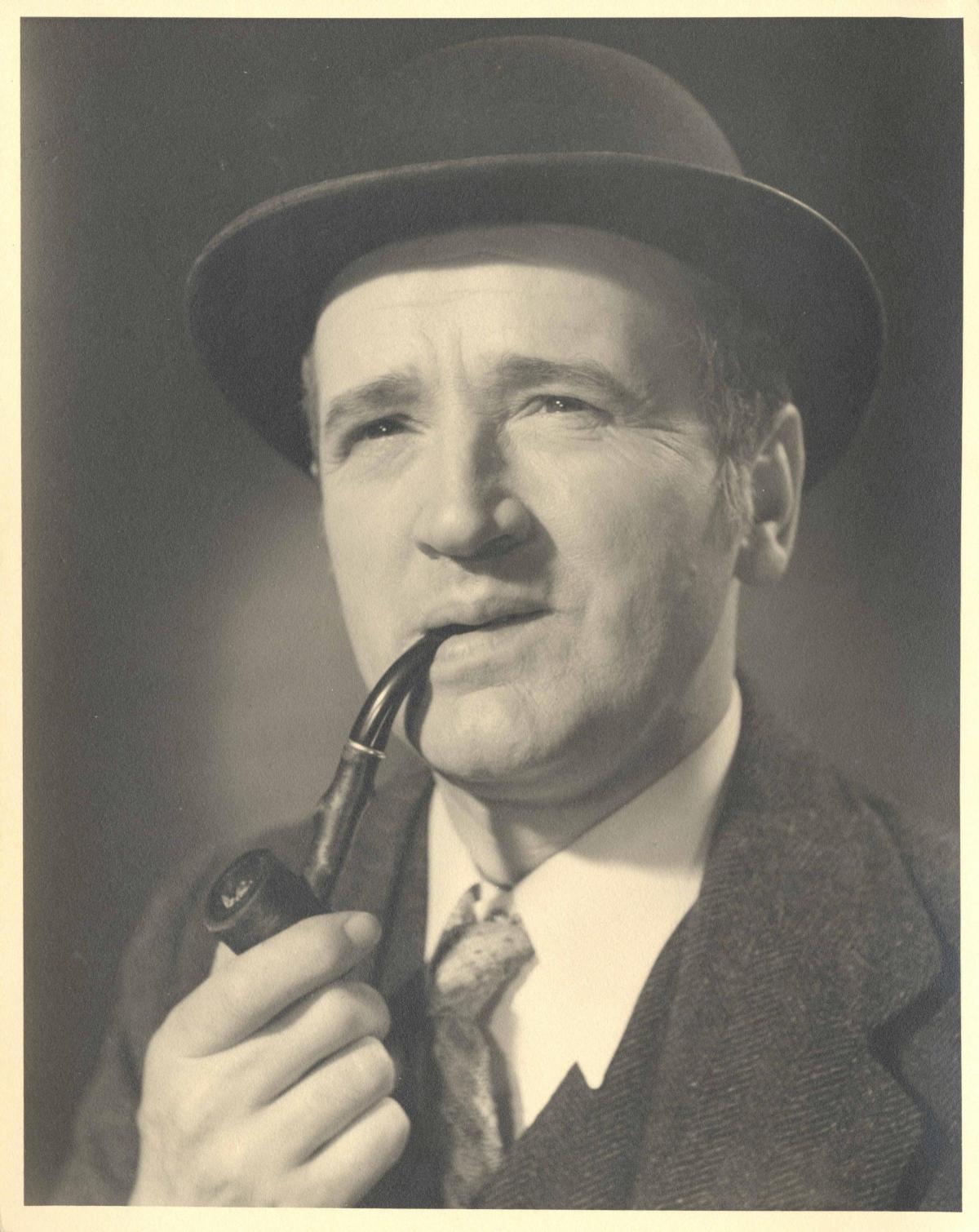

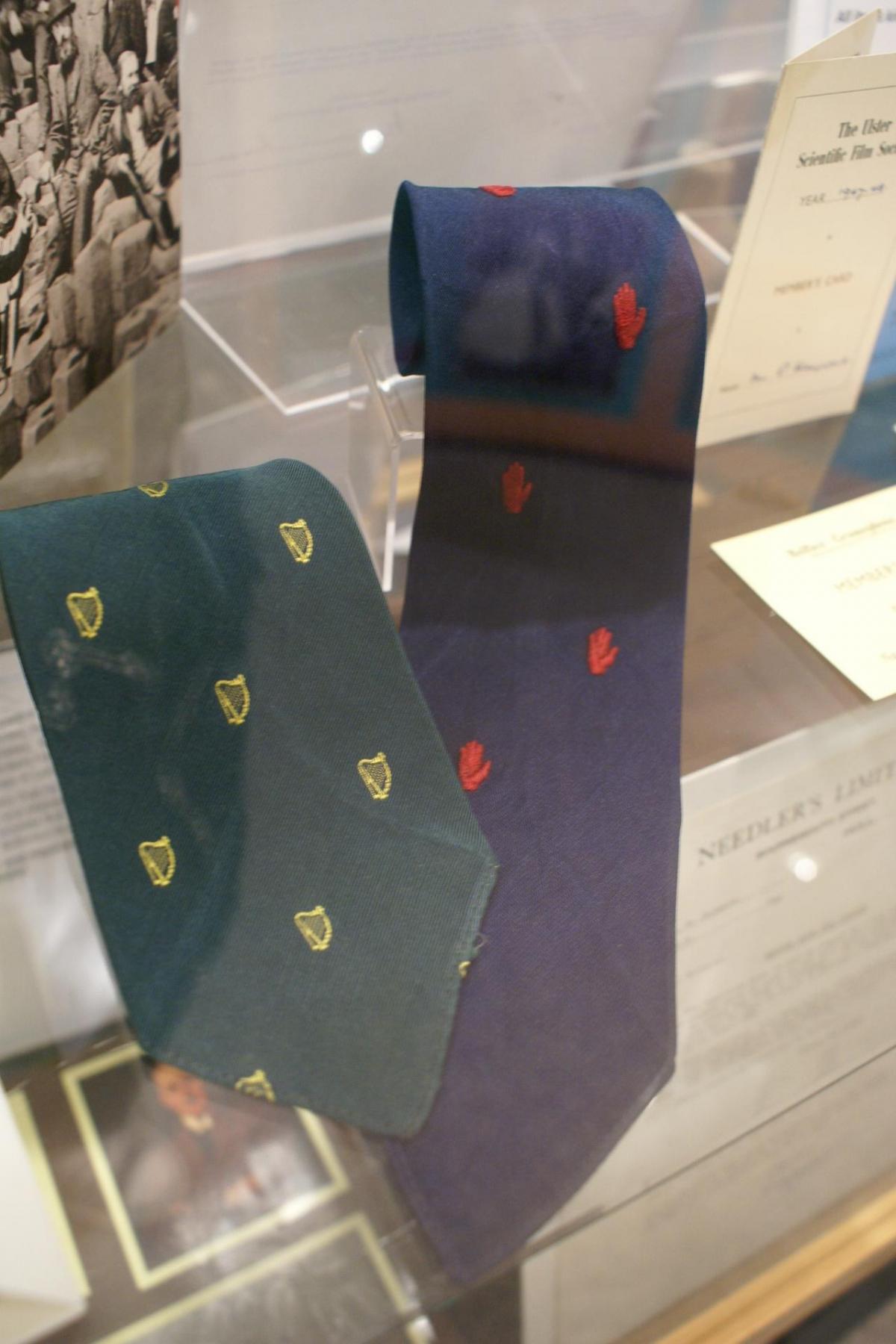

Amongst all the Hayward artefacts in the Larne exhibition, his pipe, cigarette holder and diary shared a glass cabinet with two neck-ties, a particularly telling duo.

One tie is patterned with the red hand of Ulster, the other with little green Irish harps!

For public appearances Hayward “carefully choreographed the occasion through the insignia” a label on the cabinet explained “reflecting the ties that bind the two parts of the country.”

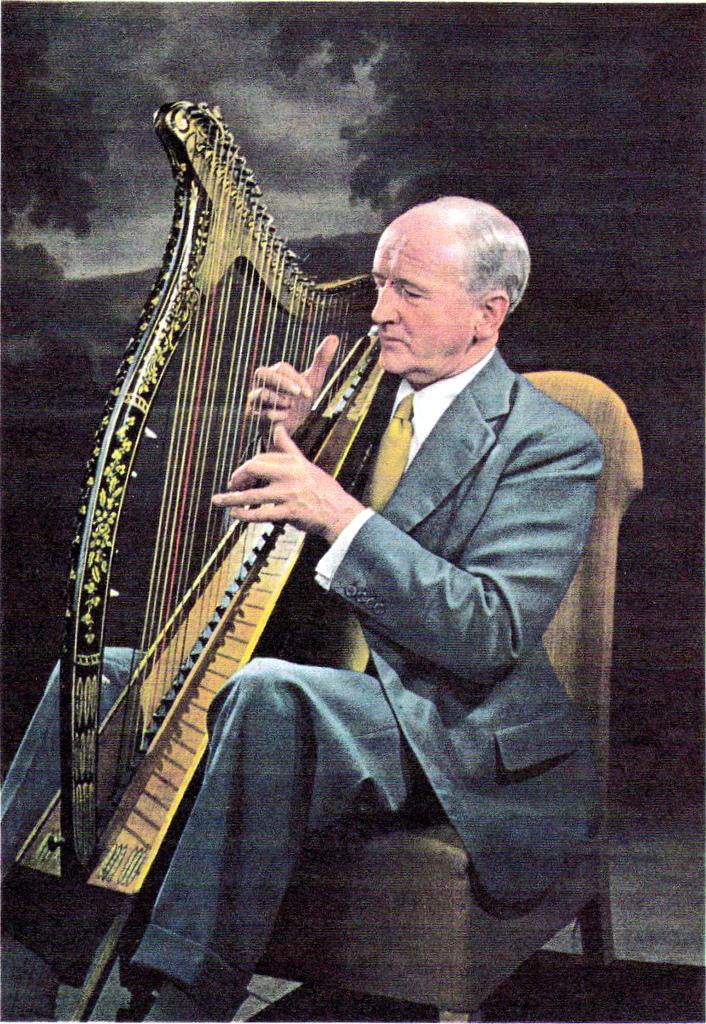

There were recordings in the Larne Museum of his excellent harp playing, compilations of his numerous records and clips from his films.

I listened to other recordings of his Orange songs and Irish ballads, and had a short chat with Ian McGimpsey, who was a 21-year-old RUC Constable on duty in Ballymena Police Station on Tuesday 13 October 1964.

“I remember it very well,” Ian told me “the Sergeant sent me to an accident on the Antrim Road.”

Arriving at the scene Constable McGimpsey immediately knew “it wasn’t good.”

There were three dead and one seriously injured in a two-car crash.

Richard Hayward’s Ford Anglia had crashed head-on into a car driven by Portrush assistant curate Rev Stanley Dunlop accompanied by his mother Violet and their housekeeper Lavinia Kew, who survived.

“I didn’t know who he was,” Ian recounted “but Richard was wearing a fawn-coloured Burberry coat.”

I also talked to Hayward’s second son Richard (Ricky) and grandson Paul whose father Dion was Ricky’s elder brother.

Richard and Paul ‘cut the ribbon’ to open the exhibition.

“I didn’t realise how unusual my father was,” Richard told me.

Why was Hayward’s name forgotten by the public for so long after his death, along with his numerous awards, honours and huge cultural legacy?

After his first wife Elma died in 1961, 70-year-old Hayward married Dorothy, 23 years his junior.

His second wife “was extremely protective of his estate and guarded his work zealously” said Paul Clements.

In trying to protect his posthumous reputation, she stifled it.

‘Romancing Ireland: Richard Hayward’ by Paul Clements is published by Lilliput Press at www.lilliputpress.ie

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here