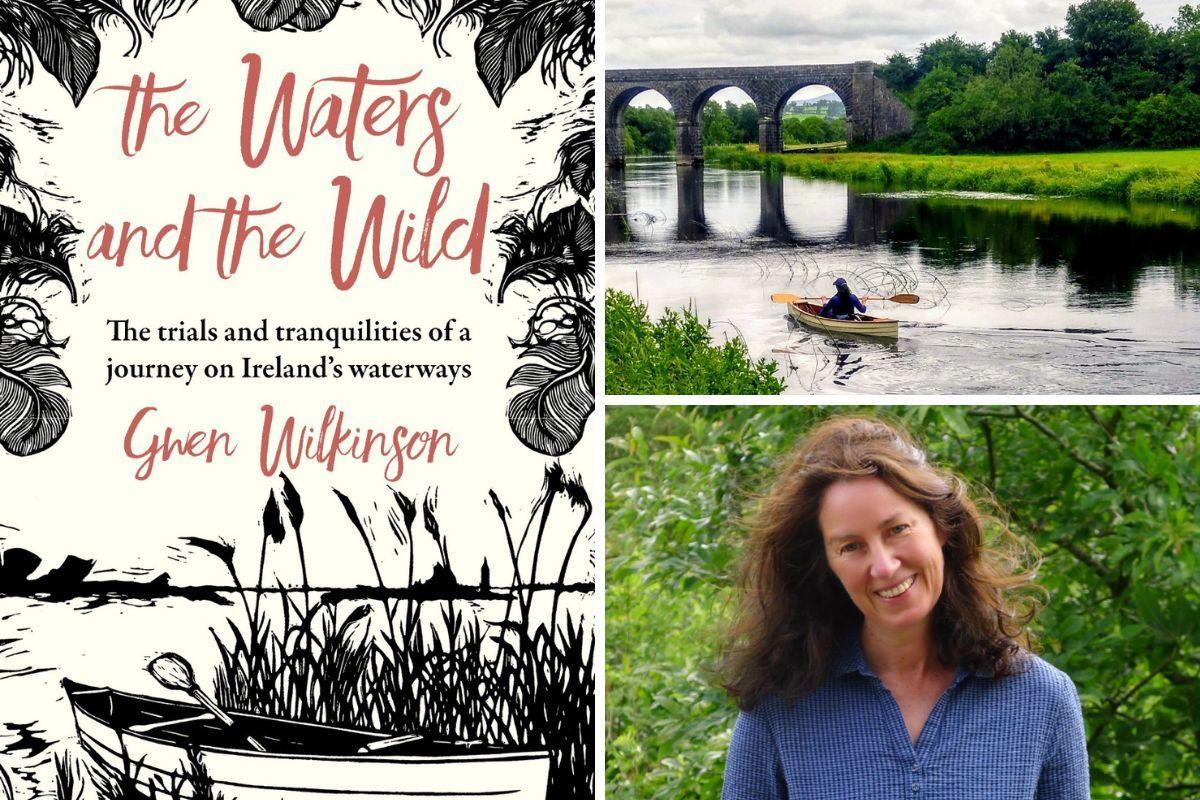

Fermanagh's Lough Erne was the key starting point of a magical journey for Gwen Wilkinson, who has documented her epic paddling adventure across the island of Ireland in a beautiful new book, 'The Waters and the Wild'.

In 2019, Gwen set herself the challenge of building a canoe and paddling it the length of Ireland, along a network of inland waterways.

She set out from the shores of Lough Erne and navigated a 400km journey to the tidal waters of the River Barrow.

More than just a travelogue, 'The Waters and the Wild' explores the interwoven histories of the people and wildlife that shaped Gwen’s journey.

As the adventure unfolds, she also shines a light on pioneering women who have left their mark on Ireland’s landscape – both natural and cultural.

Gwen has shared an extract from the Fermanagh chapter of the book titled 'Castaway, Upper Lough Erne' (widely available at book retailers) with The Impartial Reporter, as follows.

The Earls of Erne were keen yachtsmen, and for a time the boathouse was the home of the Lough Erne Yacht Club.

It would have been the venue for many spectacular regattas and boating displays. The wealthy and the privileged classes joined in from the neighbouring estates of Florence Court and Castle Coole.

It’s easy to picture the jolly scene of young ladies, bonnets tied with silk scarves beneath their chins, milling about on the terrace with the gentlemen decked out in boldly striped blazers and straw boaters, keen to demonstrate their prowess at rowing and sailing races.

A browse through old black-and-white photographs shows an impressive parade of oar, sail and steam vessels gliding around the bay

The great bulk of the Eglington, Lord Erne’s paddle steamer, dominates the scene, and floating alongside is Firefly, a smaller steam launch.

The tall masts of Zephyr and Breeze, two fast-racing yachts, rest at anchor. Nimble sailing dinghies, ‘colleens’ and ‘fairies’ hurry to and fro.

Gigs, wherries and cots were moored abreast in the shallows.

From the terrace, a paved stone slipway dips down to the water’s edge. Moored against the jetty is a pitch-black rowing boat with unusual lines, an Erne cot.

I’ve been hoping to see one since I set out on the Upper Lough. This cot is a big beast of a boat, almost twelve metres from bow to stern, and wide too.

It sits low in the water, and seems to be flat-bottomed. The squared-off bow and stern give the boat a rustic appearance.

Two-thirds of the boats is taken up with seating, long benches running parallel to the gunnels. There are two sets of oar locks.

Long before there were roads and bridges in these parts, the Erne cot was the main form of transport.

They served as passenger ferries and cargo vessels. They could even carry livestock, including cattle, sometimes up to twelve animals at a time, sheep and ponies too.

Because it has a flat bottom, the cot can navigate the shallowest margins of the river. In some cases the cot was even hauled overland with its cargo still on board, the flat bottom acting as a sleigh.

As the roads improved, the cots fell out of favour, and knowledge of their construction almost disappeared.

There has been a revival of interest recently, with the Lough Erne Heritage Group established to preserve the tradition of the Erne cot, along with other traditional boats.

The boat moored here appears to have been built relatively recently, part of an EU-funded cross-border project, according to a tiny plaque riveted to the gunnel.

The path flits by the ‘new’ Crom Castle, a Disneyesque creation that defies imagination. Vistas of the water are briefly thrown open.

In shallow bays where there is no boating traffic, mute swans linger, moorhens and their chicks embark on epic journeys. A pair of ravens, concealed in the tree canopy, honk loudly.

A kestrel balances in the air, dips a wing tip and falls away. A red squirrel streaks through the upper branches. Because the reds appear to thrive at Crom, wildlife experts have been studying them closely to find out the reasons why.

Aside from the estate being an ideal habitat, researchers have also noticed a marked absence of grey squirrels in the area, the pox-carrying grey being the red squirrel’s nemesis.

A theory has developed that the secret to the red’s success may be linked to the pine marten.

While both colour types appeal to the pine martens’ diet, field work at Crom has noted that grey squirrels dominate the pine martens’ menu.

The reds, being more vigilant than the greys, are less likely to be killed and eaten by the pine marten. It seems an unlikely alliance, but in practice it appears to work well at Crom.

The path completes its loop, returning to the harbour and camping grounds. Minnow’s slender hull chafes against the pier as the river presses heavily on her side; the current is noticeably stronger at this end of the lough.

A solo kayaker comes into view, paddling steadily upstream. The bearded boatman pulls into the quay beside me and we fall into conversation.

Steve is shepherding a group of teenagers who are kayaking around the lakes as part of the Duke of Edinburgh’s Awards.

‘Where are they all?’ I ask.

‘Oh, they’re all lost.’

I’m surprised by his nonchalance.

‘And you’re OK with that?’

‘Oh aye. It’s good for them to get lost and find their own way back. Character-building, like.’

‘A rite of passage.’

‘Aye.’

We smile knowingly.

Steve admires my canoe and seems impressed that I built her myself. And then he asks the unthinkable.

‘Can I take her out for a spin?’

This is a difficult one for me ‒ I’m very possessive of my canoe. No one but me has ever sat inside her.

I give Steve the once over; the man’s about twice my size.

‘OK then, but I can't guarantee you won't be swimming ashore!’ I let the statement hang.

Steve settles his bulk in my canoe. He paddles it out into the middle of the river and puts it through its paces; reversing, turning sharply, side-stroking, paddling very fast and rocking her violently.

I pace up and down the jetty, barely able to watch in case Minnow snaps like a twig and sinks to the bottom.

Eventually Steve returns, delighted with the experience and singing the canoe’s praises.

For a brief moment I glow with inner pride.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here