I was searching recently along the western flanks of Slieve Rushen on the Fermanagh side of the Cavan border for an ancient well, the waters of which turn wine-red every seventh year on June 23.

After finding the spring and the colourless stream that rushed from it, I cycled on for a few hundred metres until forced to stop at a cul de sac at Gorgesh.

I dismounted to enjoy panoramic views of Swanlinbar, Benaughlin and Cuilcagh Mountains to the west, Kinawley and Belmore Mountain to the north, and the Iron Mountains in Leitrim to the south.

There was something different and intriguing about this place nestling under a hill rising to its east.

Squeezed tightly against the Border only a few fields away from the end of the road heightened the sense that I had arrived at more than an unexpected destination or terminus, but of what?

There was a cluster of six or seven bungalows and several older abandoned houses close to where the road ended.

All were near to each other as if strewn together haphazardly. They did not have the appearance of a contemporary settlement – to have neighbours living cheek-by-jowl is rare in these modern times of ribbon development.

Whilst initially appearing to be a small village, it did not have a church, pub, or shop.

This place, with its array of straight-lined fields running side-by-side up the adjacent, hillside appeared to be very old indeed, and reminded me of similar settlements I had visited on the Inishowen peninsula.

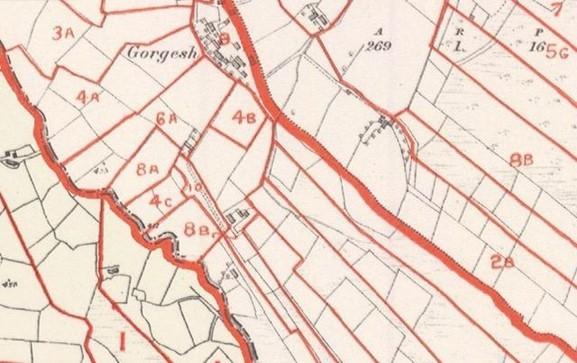

I subsequently consulted the 1832 Ordnance Survey map which showed that Gorgesh had an almost identical cluster of houses dating back to pre-Famine times.

Later maps from 1860 and 1900 again showed a comparable number of houses and layout, and importantly, details of changes to the surrounding fields which rose regimentally up the hillside above the settlement.

Evidence then that this small assemblage of houses, now nestling in a modern landscape pocked with quarries and peppered with windmills, is a survivor of a much older agricultural community known as a clachan, whose inhabitants operated an agricultural system reminiscent of rural communities in marginal upland areas found mainly in Derry, Antrim, Tyrone, Donegal, and Sligo.

Dating from the mid-18th to the mid-19th Centuries, clachans were communally regulated settlements of subsistence farmers, usually kin (in Gorgesh, they were mostly Gileeces).

They worked the land collectively using the Rundale system, based on sharing risks and benefits by annually rotating the best land among each other.

With houses huddled close together, the community farmed an open infield close to the clachan to grow crops such as potatoes and barley (which was further divided into family strips of land), and an outfield to graze cattle which were subsequently moved to the uplands in the summer, before returning in the autumn to feed on the stubble of the infield and manure it for the following season.

This off-site herding, known as transhumance, or ‘booleying’, took place in temporary upland dwellings where village herders, often women and children, looked after livestock.

In the neighbouring townland of Stramatt, there are two stone-built structures on the hill above the clachan which may have been used for this purpose.

In nearby Molly and Doon townlands, there may also be another two clachans, now much degraded and deserted.

However, inefficient husbandry and a rapidly increasing population undermined the system.

A succession of landlord- and state-endorsed redistribution schemes aimed to change the occupants of clachans into disconnected private proprietors, and from around the 1830s to the 1860s, their fate was sealed.

The desire of landlords to regulate production and improve rents ensured that land holdings were consolidated, and fields were subsequently enclosed.

Tenants were assigned land individually and encouraged to build houses linked to their reallocated sections.

Hilly areas were re-organised into long strips of interconnected fields extending from new farmhouses to poorer marginal uplands.

This stripping of the land created ladder fields which can clearly be seen today.

Communalism ended, and the individual landholding system triumphed.

Even the townland meaning of Gorgesh in Irish hints at the impact brought about by these changes; Gort: tilled field, and Geis: possibly taboo, or prohibition.

Gorgesh is a hidden gem, and a unique part of Fermanagh’s agricultural heritage. It is also a living relic of communal farming, wine-red waters, and ladder fields.

The last report of water changing colour at the well was in 1976. By my calculations, it should turn red again on June 23, 2025.

Put the date in your diary, and I will see you there. Bring a wine glass.

This, and previous Impartial Reporter articles, can be read at https://notes-from-the-field.blog.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here