Ahead of World Suicide Prevention Day, Monday the 10th September this year, local sports stars from different backgrounds including football, rugby and GAA came together to mark the occasion. Spelling out the word ‘Hope’ in jerseys in front of Stormont’s steps, they remembered the 305 people who lost their lives to suicide in Northern Ireland in 2017 alone. That’s on top of the 297 lives that were lost in the year prior, a figure that has crept upwards in a worrying trend over the past decades, to epidemic proportions.

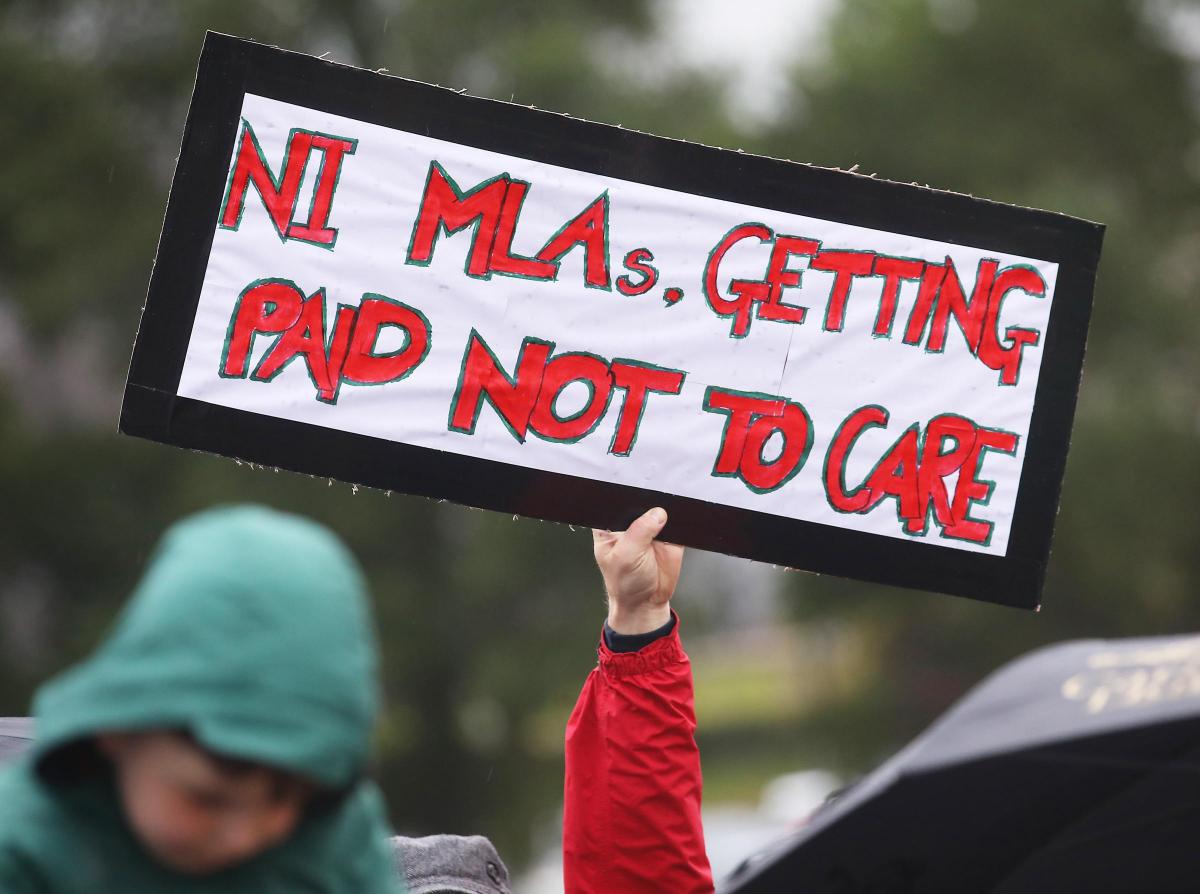

And while this gesture outside NI’s parliament buildings is no doubt driven by a heartfelt desire to spread awareness, break down stigma and reach out to support those who are suffering from mental health problems, it’s difficult to ignore the irony. How much hope is there for people who are struggling as long as Stormont stays empty, and funding for our health services remains strangled?

It’s incredibly frustrating, and sometimes even upsetting, to think about how the people in Northern Ireland are being forgotten, left behind and failed. While increased funding is being injected into mental health services in England and the rest of the UK, Northern Ireland remains stuck – despite mental illness being 25% more prevalent here than in England. Meanwhile, roughly 300 people a year are losing their lives, and up to 25 times that number of people may be attempting suicide per year, Samaritans estimates. In Northern Ireland, up to one in five adults is dealing with a mental health problem at any one time – which is over 200,000 people.

All of this can seem to paint a picture of hopelessness for the future of our mental health services, and for the possible outcomes and wellbeing of each and every individual who seeks help. But while there are mountains ahead of us still to be tackled when it comes to how far we have to go, we mustn’t forget just how far we have come. Thanks to hard work by local mental health charities, and by ordinary people opening up about their experiences with mental health, the stigma and myths surrounding the subject have gradually begun to be broken down. Our society and communities have become more and more open to the message that it’s okay not to be okay. And while it certainly doesn’t replace the need for professional care and help when someone is experiencing mental illness, ordinary people coming together can without a doubt make a difference.

A perfect example of how small actions by our communities can actually save lives was the messages of hope which were attached to trees and left scattered around Cavehill in North Belfast, an area with some of the highest levels of suicide in the North of Ireland. The messages of hope managed to catch the attention of a young man last week who was in a dark place. He was convinced to call the number, and to ask for help. As a result, a life was saved from suicide. It may be just one less, but if just one life could be saved every day here, we could have a Northern Ireland free from suicide.

This was the message behind this year’s World Suicide Prevention Day - working together to prevent suicide. While we're not expected to be experts, and once again, not expected to replace the need for professional help, there are small, tiny things we can all do to try and help. Knowing the possible warning signs for suicide are essential, and fairly simple to keep under your hat – somebody talking about death or dying, even in a joking way, or speaking about having no purpose, being trapped or being a burden to others can be big red flags. Sleeping too much or too little, and being agitated, using drugs or alcohol more, or being anxious, very angry or extremely moody can also be warning signs. Withdrawing from social situations or isolating themselves can also be a symptom to look out for – if you find a friend never shows up to nights out anymore, or a family member hides away in their room or their home often, be sure to check on them. If you’re concerned about someone, something as small as asking them how they are and really meaning it can start a conversation about how they may be feeling. Now, the issue usually is, as a population we’re not well known for our ability to open up or to have a direct conversation about anything, really. When we’re asked how we are, the usual acceptable and expected response is something like “ah, sure you know yourself”, or a basic “grand”, or one that I personally absolutely despise – “Sure there’s no point complaining, nobody listens to me anyway!” We need to ask the question and really mean it - and charities like Samaritans recommend you be direct. Asking someone if they're thinking about suicide, or if they have a plan, is unlikely to put the idea in their head - but it's effective at helping people to open up. And for someone who feels alone, and trapped, just starting a conversation may be the first step towards getting some extra help.

And if you want to make a little bit of difference, there are many amazing mental health charities across the UK and Ireland who rely on donations to provide services to help those who are struggling – even just a small donation can go a long way to helping charities continue their vital work. And in the absence of any leadership from the top down, we have to have each other’s backs – and we need to support those organisations that are struggling on despite the absolute drought on the funding front.

If you’re struggling, Samaritans (116 123) or Lifeline (0808 808 8000) are available to call, text or email 24/7 and you can speak to a trained listener or counsellor. It’s okay not to be okay, and there’s always somebody there to listen. You’re not alone.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here