If this year’s worldwide total of 8.3 trillion text messages sent from mankind’s collective hand-held devices could be batched together they’d fade into insignificance compared with one short message in French sent by Morse code at around 6 am on 11 November 1918 - a century ago this Sunday.

‘Dot dash dot dot dash…’ the message began, “les hostilités seront arrêtées sur tout le front à partir du 11 novembre à 11 heures, heure française” which, decoded and translated, means “the hostilities will cease along the whole front from 11 November at 11 o’clock, French time.”

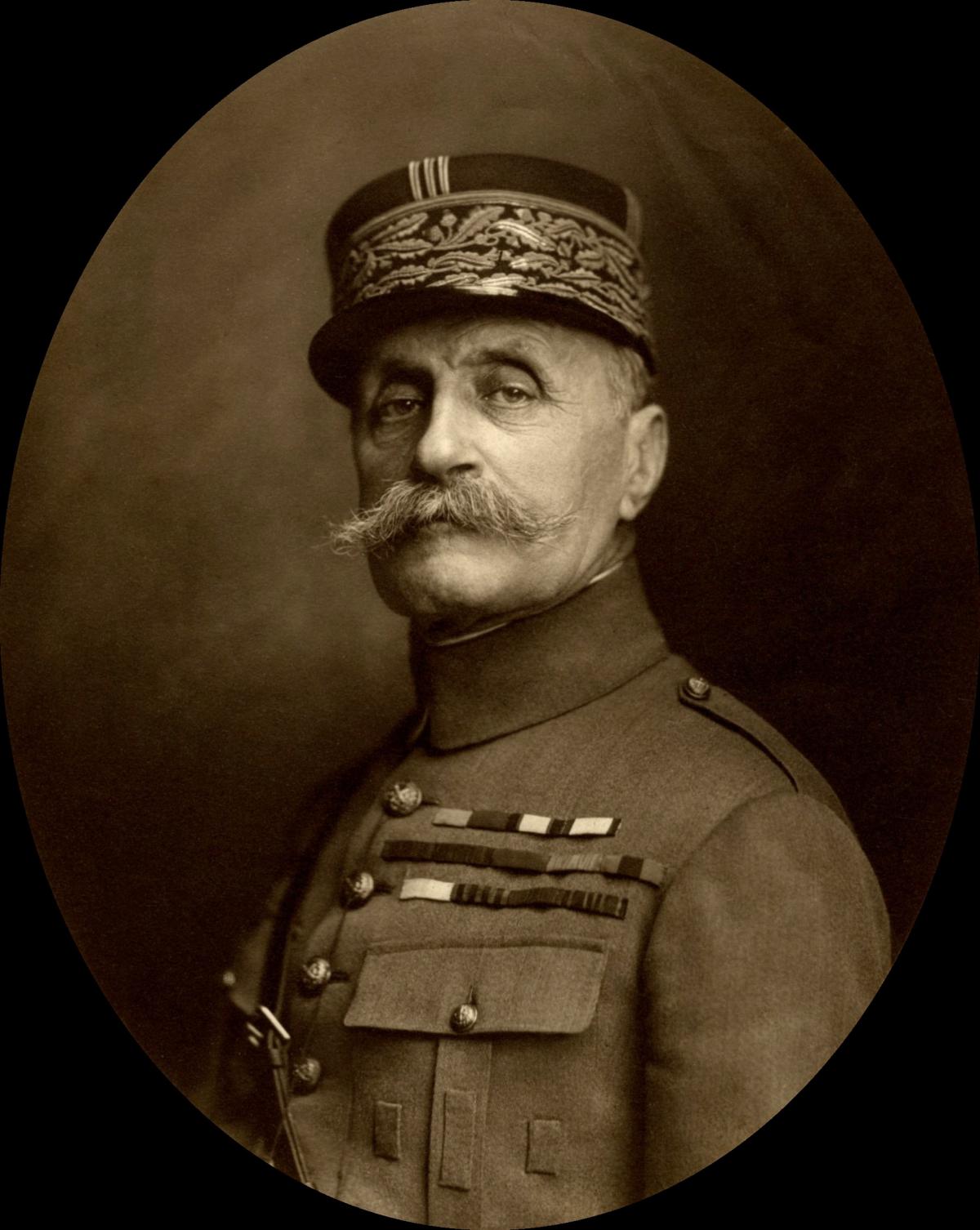

The message, from France’s Marshal Ferdinand Jean Marie Foch, announced the end of the First World War, a global conflict which cost some 10 million military lives, 21 million military wounded, eight million soldiers missing or captured, nine million civilian casualties and up to 100 million deaths in the post-war influenza pandemic.

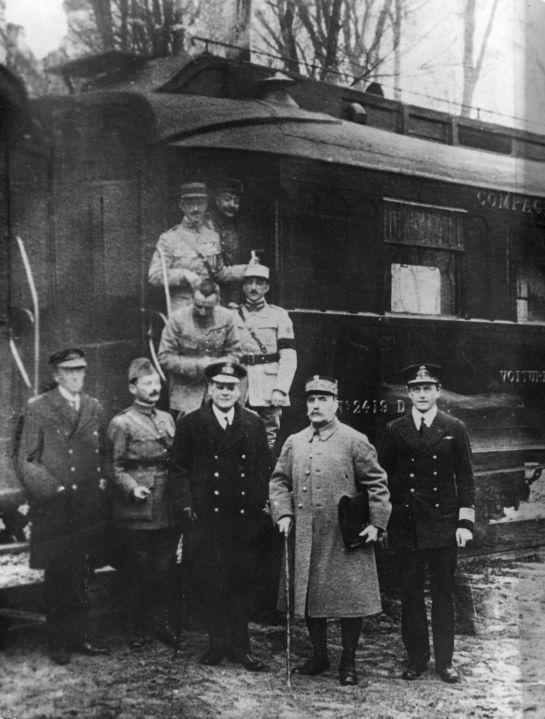

Marshal Foch signed the Armistice in a railway carriage in the remote Forest of Compiègne, some 37 miles from Paris.

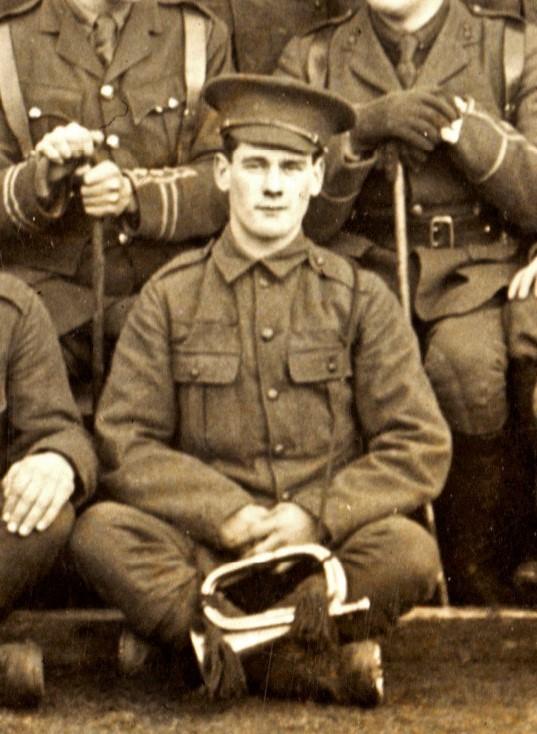

His signature came too late for George Emmett from Enniskillen, John McCaffrey from Springfield, Alexander Armstrong from Maguiresbridge, John Connolly from Newtownbutler and Thomas Smyth from Lisbellaw, who,

besides their heroism and Fermanagh addresses, shared a common, tragic trait - they were just 19 years old when they died on the front lines between 1914 and 1918.

James Carlin from Brookborough, William Morrison from Florencecourt and William George Threadkill from Enniskillen were just 18 when they died, and Robert Cousins from Kinawley and John Cairns from Enniskillen were only 17.

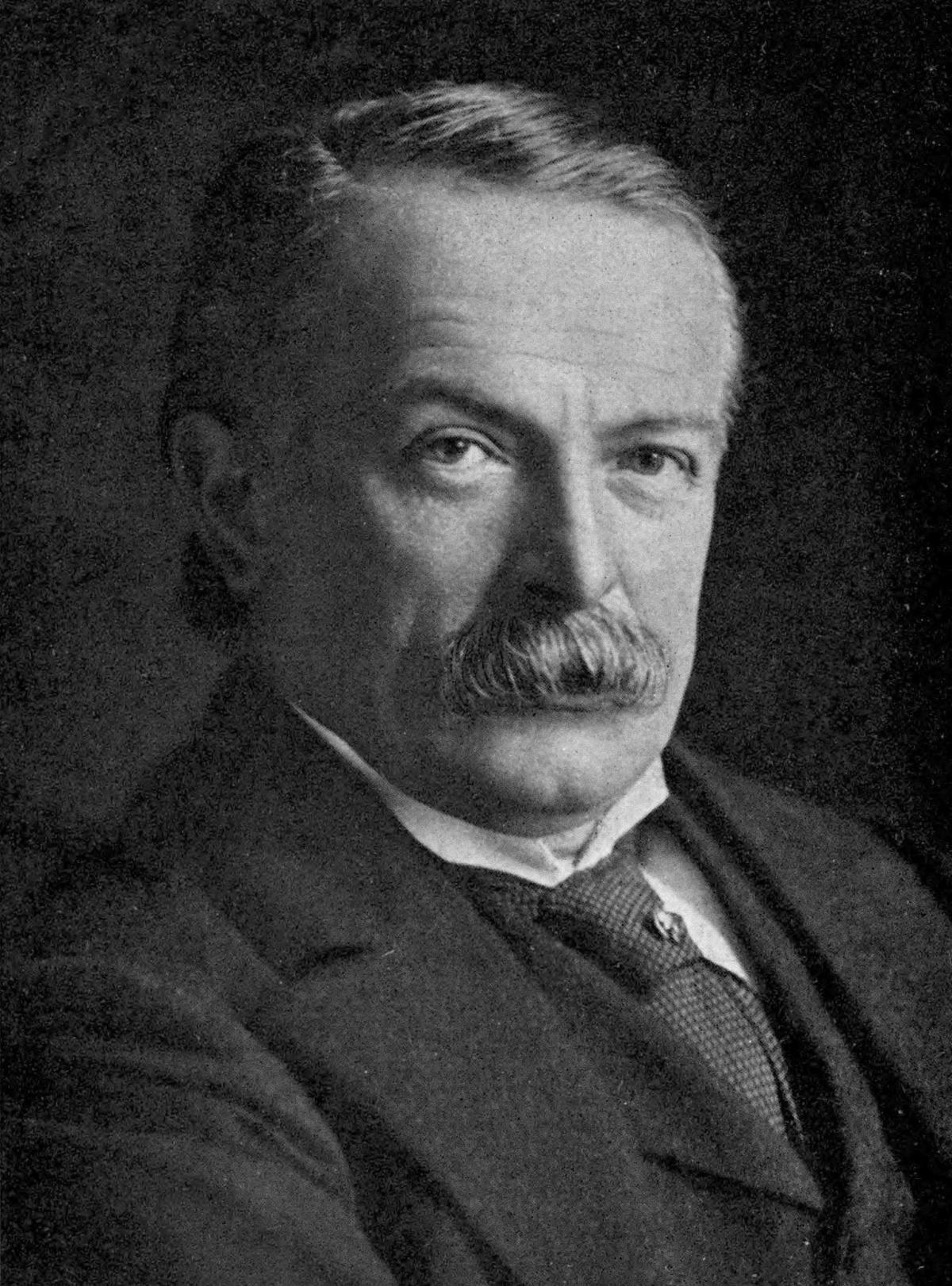

British Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey famously announced on the eve of the declaration of war in 1914 - ‘The lamps are going out all over Europe, we shall not see them lit again in our lifetime.’

The tragic loss of lives, particularly of young men and boys, was the dark cloud overshadowing the world at the end of WWI.

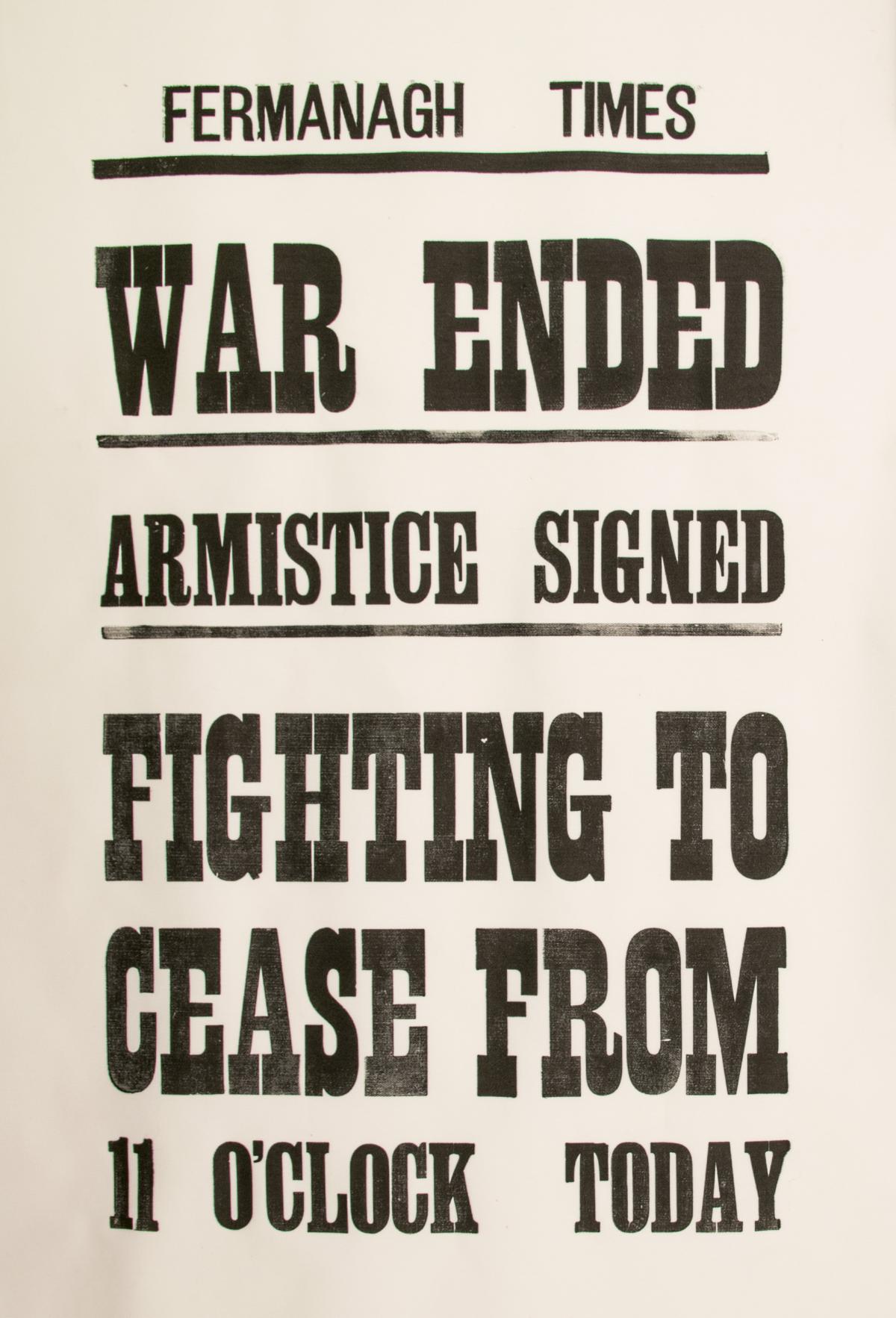

The Armistice was a silver lining, celebrated in Fermanagh before anywhere else in Britain and Ireland.

A wireless operator in Enniskillen’s military barracks intercepted Marshal Foch’s faint Morse code message around 6 am and by the time Prime Minister David Lloyd George announced the Armistice at 10.30 am, Fermanagh and its adjoining communities had been rejoicing for three hours.

The clock in Enniskillen Police Station, formerly the military barracks where Marshal Foch’s message was intercepted, will be illuminated this Sunday at 7pm and St. Macartin's Cathedral, where the bells tolled the first news of the Armistice, will have its clock lit up for the first ever.

The clocks will remain illuminated thereafter, symbols of peace and hope within a local community that celebrated together when WWI ended, as old press cuttings recount:

‘Kilskeery and neighbourhood entered into the spirit of rejoicing with much enthusiasm.’

‘The bells of St James’s Church of Ireland and St Mary’s Roman Catholic Church in Aughnacloy rang merry peals and continued at intervals during the day.’

There were bands, bonfires and torchlight processions in Maguiresbridge where people ‘were no whit behind those residing in larger and more populous centres in expressing their joy and relief at the cessation of hostilities.’

In Blacklion and Belcoo ‘all political parties combined in the most friendly manner to celebrate. Possibly in no place in Ireland,’ a newspaper proclaimed, ‘was there such unanimity displayed by all sections of the community. Musicians of the Nationalist band weren’t of sufficient numbers whereupon those of the Protestant band stepped into their places and were hailed with a céad míle fáilte!’

Church bells rang out in Enniskillen, described by the Impartial Reporter as ‘Joy Bells’.

Island-dwellers and local folk ‘for miles around learned of the good news of the termination of the war by the firing of guns and the discharge of rockets from the military barracks. Factory sirens hooted, Enniskillen was thronged and people rejoiced and shook each other’s hands heartily on account of the good news.”

Ballinamallard was ‘early astir and several triumphal arches were erected across the street and every house showed from one to five or six handsome flags.’

This week’s centenary commemorations, here and around the world, are part of a global event collectively called ‘the Battle's Over - A Nation's Tribute’.

Enniskillen, like larger and smaller communities around Fermanagh and Northern Ireland, will join in a special programme of talks, exhibitions and memorial events.

The town’s Centenary Remembrance Sunday starts at 6am.

Around the UK 1,000 lone pipers will play ‘When the Battle’s O’er’, a traditional tune played after a battle which will also be played at Enniskillen Castle at 6am prior to an extended programme of commemorations, church services, bell-ringing, bugle calls, pipes and drums in the street, illuminations, fireworks and beams of light into the night sky.

Full information on the Commemorative events in Enniskillen is at http://www.inniskillingsmuseum.com/armistice-2018/

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here