Dr. David Morrison

Counselling Psychologist

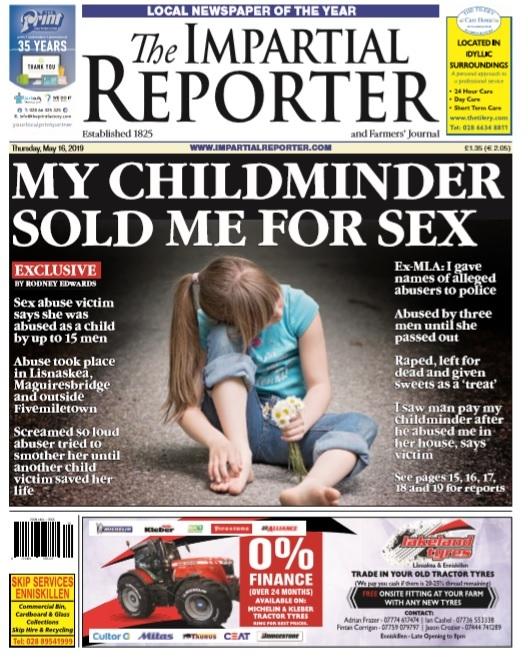

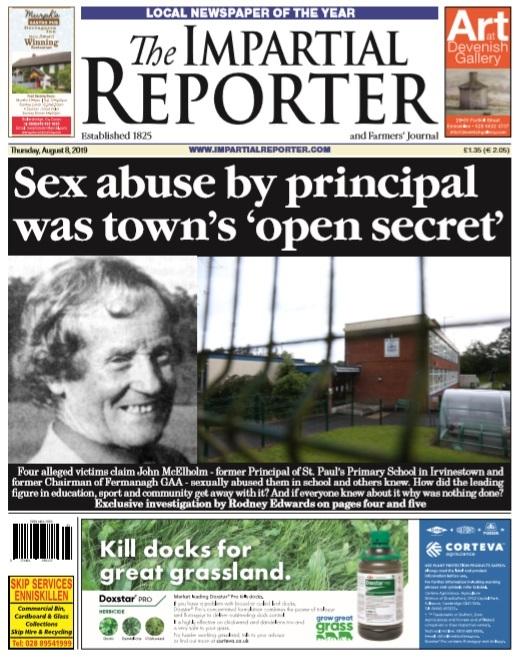

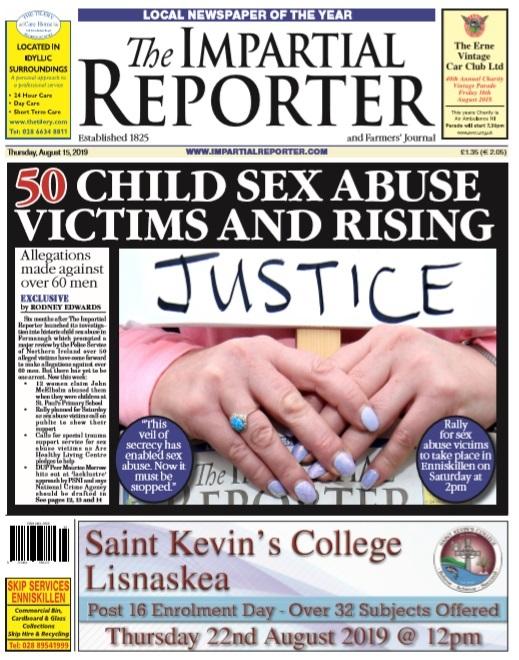

Almost 70 alleged victims of historical child sexual abuse have now come forward to The Impartial Reporter over the last 9 months. It has been heartening to see an outpouring of support for these courageous people, including a packed public meeting in Enniskillen on 29th October which I was fortunate to attend.

At the public meeting, a member of the public asked the panel what we would like to see from elected officials. With a general election just weeks away, this is a golden opportunity to think about changes to policy, funding and legislation which might help victims and survivors of child sexual abuse. In my reply, I suggested five questions which I think concerned citizens of Fermanagh and South Tyrone should be asking candidates who want your vote on 12th December:

1. What will you do to tackle the low rate of convictions for child sexual abuse and other sexual offences?

As readers of The Impartial Reporter in recent months will know, there are a number of reasons why young people do not disclose abuse when it happens to them. Victims may feel ashamed and blame themselves for the abuse. They might be concerned that no-one will believe them. They may even fear the disclosure could harm themselves or people they care about.

In some cases, young people overcome these concerns to tell a responsible adult who then challenges or ignores the disclosure. In other cases, the abuse is addressed without involving the police or social services.

For these reasons, estimates suggest that as few as one in eight cases of child sexual abuse come to the attention of the authorities.

Reporting a sexual offence requires incredible courage from victims. It demands an equal measure of determination: for complex or historical cases, the police investigation and decision to prosecute can take between one and two years. For some victims, the journey proves too long and too painful and they drop their case.

For victims who persist, the likely outcome is not promising. From October 2018 to September 2019, 3,383 victims reported alleged sexual offences to the PSNI; 2,004 of these were children and young people up to 18 years old.

After the police investigation, around half of cases involving alleged sexual offences are dropped due to insufficient evidence of a crime being committed. Of those that remain, some don’t proceed because the Public Prosecution Service (PPS) decides that a prosecution is unlikely, and some because the victim decides to drop the charges.

By the end of this process, just 15% of the 3,383 cases involving victims of sexual offences led to a charge/summons or sanction against the suspect. Around 60% of prosecutions ended with a conviction.

At every stage - reporting, investigation, prosecution, and conviction - the numbers dwindle. By the end, fewer than 10% of victims secure a conviction. For the 90%, the lack of a conviction can lead to regret that they put themselves through a long, difficult process ‘for nothing’. It can perpetuate - even deepen - the sense of powerlessness and hopelessness that victims felt for so long. More broadly, it undermines public trust in the criminal justice system and discourages other victims from coming forward.

We need to ask our electoral candidates: what will you do to change this?

2. Will you support a change in the law to make it easier for victims of historical child sexual abuse to pursue civil action against alleged abusers?

Victims of child sexual abuse can pursue civil action for compensation from their alleged abusers. This is a separate process to criminal proceedings. A civil action can take place in parallel with a criminal prosecution or instead of a criminal prosecution, or when criminal proceedings have concluded with no prosecution or a prosecution ending in either acquittal or conviction.

In criminal prosecutions, the case must be proved ‘beyond reasonable doubt’ - a jury must be sure that the abuse happened. This is part of the reason there is such a low rate of convictions. In civil claims, the court need only be persuaded to the lower standard of ‘on the balance of probabilities’, which means that it was more likely than not that the abuse happened.

Civil claims can be made against the alleged/convicted abuser or against those individuals or organisations which are vicariously liable for their actions. For example, a school where the alleged/convicted abuser worked as a teacher.

Where criminal proceedings have not resulted in a conviction, civil action offers a ‘second chance’ for justice. However, very few victims pursue civil action. In some cases, this is because victims invest all their energies and hopes for justice into criminal proceedings. By the end of the difficult criminal process, the prospect of civil action is a bridge too far.

For historical cases of child sexual abuse in Northern Ireland, there is another reason: they can’t. As the law stands, victims of child sexual abuse must begin a civil action no later than 3 years from their 18th birthday. In exceptional cases, victims can apply for this to be extended “where material facts are not known”.

As we know, victims of child sexual abuse can be much older than this before they disclose abuse (if ever). There are well-documented and understandable reasons for this. This delay already means that criminal proceedings in historical cases are less likely to result in a conviction compared with current or recent cases of child sexual abuse. Under the current legislation, this delay means that victims will also not be able to pursue civil action.

This barrier to justice can easily be removed. In 2017, Scotland did away with the 3 year time limit for victims of child abuse. Victims of child abuse in Scotland can now pursue civil action as adults at any time. They can also apply for civil legal aid for help with the costs of this. This is an example Northern Ireland can and should follow.

A change to the law would offer a ‘second chance’ for justice to the alleged victims of historical child sexual abuse in Fermanagh and elsewhere in Northern Ireland. In recent months, we have read how many of these alleged victims were told there was not enough evidence for a criminal prosecution. The ongoing police investigations and reviews may see some of these decisions reversed. In any event, some alleged victims could already begin civil action if the 3 year time limit were removed.

There are drawbacks to civil cases for child abuse. They take longer than criminal proceedings, lasting anything from 2 to 5 years. And without a conviction and prison sentence, the justice it offers may not be enough for some victims. However, the lower burden of proof means they are more likely to succeed.

If you want to give victims this ‘second chance’ for justice, ask your politicians to follow Scotland’s example and remove the 3 year time limit for civil action.

3. Will you campaign to change the guidance around pre-trial counselling for victims?

Disclosing abuse to the police can understandably be a distressing experience. It can bring up memories that have remained hidden or buried for many years. At this point, it may be helpful to undertake counselling. In other cases, victims are already undertaking counselling and it is the counselling that has encouraged them to finally tell the police what happened.

In either scenario, once a criminal investigation or prosecution is underway, the counselling becomes constrained by the guidance of the criminal justice system. The counselling sessions can be used to help the victim with their self-esteem, reduce distress about legal proceedings, or address the emotional and behavioural aftermath of the abuse. The one thing the counselling can’t do is allow the victim to talk about the abuse itself. Which is, unsurprisingly, often the one thing victims want (and need) to do most of all.

There are two main reasons for this. First, it leaves the prosecution open to accusations that the victim has rehearsed their evidence in advance of a trial, or that the conversations in pre-trial counselling have ‘contaminated’ the victim’s evidence. Second, the benefits of talking about the traumatic incident in pre-trial counselling can create the appearance of the ‘unbelievable victim’ in court: a victim who is able to talk about the abuse or respond to cross-examination in a relatively calm and coherent manner.

Both these justifications can be challenged. First, a psychological therapist with appropriate training in pre-trial counselling will be able to work with victims in a manner that does not contaminate their evidence. For example, a therapist who allows victims to volunteer information about the incident but does not prompt for further information will reduce or eliminate the risk of ‘implanting’ false memories into the victim’s account.

Second, the idea that a calm and coherent victim is ‘unbelievable’ illustrates just how poorly the criminal justice system understands trauma. Victims may be understandably distressed when talking about their abuse. Others will feel nothing at all - just a numbness. Many will be somewhere in the middle. Apparent distress levels are not a reliable indicator of the truthfulness of victims’ accounts and should not be used as a justification for preventing victims from talking about the abuse in pre-trial counselling.

Victims may reach a point where they must talk about the abuse in pre-trial counselling for the sake of their mental health. This is a particularly high risk in complex or historical cases that can take a long time to go to trial. But in so doing, victims run the risk that the prosecution service will drop their case or that the prosecution will not be successful. Put simply, victims may have to choose between mental health and justice.

This issue is not limited to Northern Ireland: the same limitations apply in guidance from the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) in Britain.

It doesn’t have to be like this. Mental health and criminal justice professionals can work with victims to change this guidance. For example, we could allow for unrestricted counselling from appropriately trained mental health professionals. We could train criminal justice professionals and jurors on the psychological impact of trauma, and how counselling can help change victims’ responses to the traumatic memories without affecting the contents of those memories. There is no reason victims can’t have both the mental health and justice they deserve.

4. Will you campaign for reform of the criminal compensations process for victims of child abuse?

If victims are unable to claim compensation from their assailant, they can apply to the government-funded Criminal Compensations Agency. For some, it can offer a sense of closure - especially in cases where criminal or civil proceedings have not taken place or failed to produce a guilty verdict.

Unfortunately, some victims report that the application process can take a long time - perhaps a number of years for complex cases or where cases are appealed.

The process also forces victims to relive their trauma and its impact at multiple assessment sessions. For instance, victims may be asked to undertake assessments by a psychiatrist, medical doctor, educational psychologist, clinical psychologist, and financial impact assessor.

Some victims report receiving an initially low offer of compensation which they then have to challenge with legal action in order to obtain a fairer compensation figure.

In addition, any compensation received can have an impact on means-tested benefits.

For many victims of child abuse, the Criminal Compensation Agency is their ‘last resort’ for justice. But for too many victims, this justice is hard-won. We need to ask our politicians to campaign for a compensation process that is quicker and more compassionate for victims of child abuse.

5. Will you ensure that voluntary sector organisations receive government funding to help them cope with the increase in demand for their services?

Many of the victims - both those who have come forward and those who haven’t - may need support in the time ahead. This is an unprecedented crisis and we need to make sure that support organisations have the capacity to cope with it. At times like this, the focus rightly turns to statutory services like the NHS. But we must not forget the voluntary sector organisations who so often pick up the slack left behind by underfunded and oversubscribed public services, often without a penny of government funding.

We must recognise their vital role in the time ahead and the exceptional nature of the circumstances. To this end, government funding should be ring-fenced for voluntary sector organisations in Fermanagh who are struggling to cope with the increase in demand. This will ensure that these invaluable organisations can continue to provide a high-quality service to victims of historical abuse and anyone else who needs it.

These are five questions you might like to ask when someone comes looking for your vote. You may have questions of your own to add to the list.

Three months ago in this newspaper, I wrote that “child sexual abuse has been, and remains, a silent and hidden epidemic”. The ‘epidemic’ in Fermanagh is no longer silent and no longer hidden. Now the courage of the victims needs to be matched by the courage of the politicians. They can act to help the alleged victims. They can act to help future victims. We must demand that they do.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here