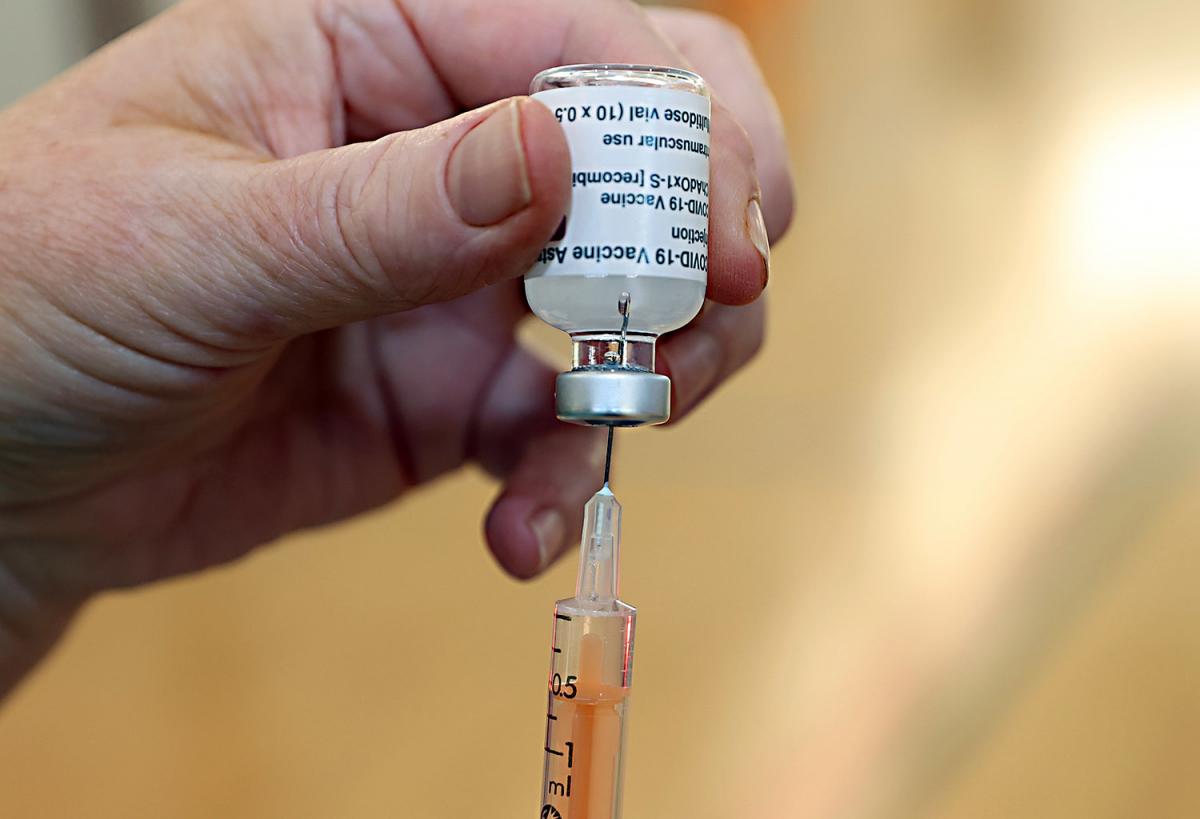

“YOU’LL only feel a wee scratch,” said my doctor before my Covid-19 vaccination jab.

I felt nothing at all, and marvelled at the march of medicine!

English physician Edward Jenner – the acknowledged founder of vaccinology in the Western world – inoculated eight-year-old James Phipps with vaccinia virus (cowpox) in 1796, the world’s first immunisation, in that case against smallpox.

(Anti-vaccinators of the time spread scare-stories about cow-like appendages sprouting from the bodies of people he vaccinated!)

Dr. John Crawford, born in Northern Ireland in 1746, introduced advanced smallpox inoculations to America, applied without today’s slender, metal needles. Ouch!

The ongoing roll-out of Covid-19 vaccinations here and around the UK has reached awesome proportions, burgeoning rapidly around the world, though remaining fearfully small in many countries.

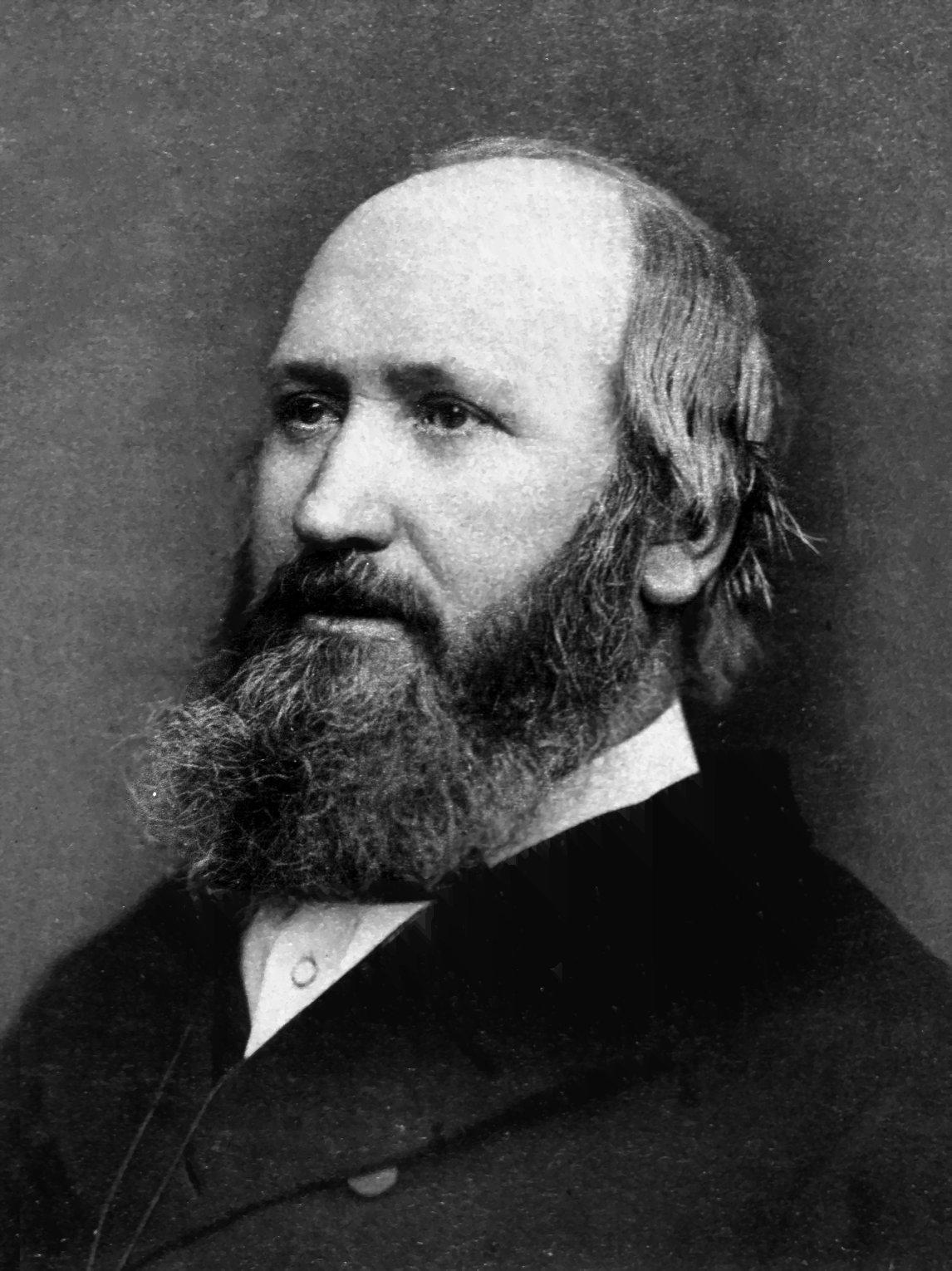

These unprecedented vaccination statistics are only possible because of an Irish surgeon and physician, Francis Rynd, who was born in Dublin in 1801. (Several accounts give him Fermanagh connections.)

Some biographers highlight Rynd’s student days in Trinity College Dublin, where he preferred socialising and fox hunting to studying medicine!

However, according to the authoritative Lancet medical journal, Francis Rynd “made subcutaneous injections” to a woman patient in 1844 for neuralgia (chronic pain), using a ‘syringe’, described as a “slender trocar and cannula” – a metal awl for cutting into the skin, and a hollow tube.

“It was inserted subcutaneously,” the Lancet recounts, “and the trocar retracted by means of a spring. Narcotic liquid descended from the hollow handle into the puncture site as the instrument was withdrawn.”

Rynd was treating a woman who had suffered for years with severe facial neuralgic pain.

She’d been prescribed a solution of morphine, taken by mouth, to kill the pain, which had failed miserably.

So Rynd put the morphine directly under her skin, close to her facial nerves.

He had designed his innovative hypodermic needle, and on June 3, 1844, performed the world’s first ever subcutaneous (or hypodermic) injection, basically giving his patient what today would be regarded as a powerful local anaesthetic.

His syringe incorporated two standard medical implements – a trocar (cutting device) to puncture the skin on the woman’s face, and a cannula (small tube), which allowed the morphine to flow under her skin.

Article

In an article headlined “Neuralgia, Introduction of Fluid to the Nerve” published in 1845 in the Dublin Medical Press, Mr. Rynd was reported as saying that the woman slept well after the procedure, for the first time in months.

For six years previously, after falling off a wall, 59-year-old Margaret Cox had been in acute pain “over the entire left side of her face ... [with pain] shooting into the eye, in the cheek, along the gums of both upper and lower jaw”.

The Dublin Medical Press described Hynd’s procedure as “a solution of 15 grains of acetate of morphia, dissolved in one drachm of creosote, that was introduced to the supra-orbital nerve, and along the course of the temporal, malar, and buccal nerves, by four punctures of an instrument made for the purpose”.

It continued: “In the space of a minute, all pain – except that caused by the operation, which was very slight – had ceased, and she slept better that night than she had for months.”

Surgeon Rynd’s new procedure was soon used widely to treat pain, and was championed around the world as “the greatest boon to medicine since the discovery of chloroform”.

Florence Nightingale benefited from it herself during an illness, and declared: “Nothing did me any good, but a curious little new-fangled operation of putting opium under the skin, which relieved [the pain] for 24 hours.”

Academic paper

An Edinburgh physician called Alexander Wood (1817-84) was the first to properly publish an academic paper on the ‘subcutaneous therapeutic injection of drugs’, in 1855.

He used one of the “elegant little syringes constructed ... by Mr. Ferguson of Giltspur Street”, and was thus championed as the inventor of the hypodermic syringe.

In Rynd’s initial design, the liquid being injected simply flowed slowly out of the needle under gravity.

In 1853, a plunger was added to the syringe, allowing for a faster injection, directly into a vein, against the flow and pressure of the blood.

Blood tests

So, Francis Rynd should also be thanked for making blood tests possible – the addition of the plunger allowed the taking of blood samples, which could then be subjected to diagnostic tests.

After his invention became a vital tool in hospitals and surgeries, Rynd held a prominent presence in Ireland’s medical and social circles.

A history of the Meath Hospital and County Dublin Infirmary where he worked, published in 1888, records that “Francis Rynd was a perfect gentleman, and had very polished manners; he mixed in the best society, had most of the nobility in Ireland among his patients; dressed most fashionably, and was a great favourite with the ladies.”

Francis Rynd died in Dublin in 1861.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here