The great 19th Century 19 English theologian, Cardinal John Henry Newman, once said that the definition of a gentleman was “one who never inflicts pain”.

That being so, then the one and only Harold Johnston from Florencecourt/Blacklion is both a gentleman and a gentle man.

The ancient Irish would have described him as a duine ildánach, or a ‘man for all seasons’ – or, as this writer’s late father would say, “he could take tae with anyone”.

Harold is also a scholar – an historian, a leisurely raconteur, a local savant, a chronicler and a philosopher who loves people and words, and paints elegant pictures of the past as he tells The Impartial Reporter about just some of his impressive 78 years on earth in and around the Cavan town of Blacklion.

Harold has a pretty forensic recall of the stories of the days when the town was black with cattle; with American soldiers in the Second World War who could buy local ladies stockings, cigarettes, chewing gum and candy during the Second World War; of the 1970s, and the armies of the Republic of Ireland and Britain, the Customs men from both jurisdictions, the RUC and a permanent Garda checkpoint where “some of them met their future wives at the checkpoint” – not to mention the IRA, who were attacking Belcoo barracks.

The Troubles left their mark on his home place, but Harold has stayed the same and is highly respected by all – a kind, sensitive man who has a warm welcome for all.

Harold has seen all of this with calm, compassionate eyes. He’s a Border man who loves his native place, and a man who crossed all boundaries.

Listening to him is like rambling down leafy country lanes with Harold weaving some magical tales from his eclectic lifestyle which do not have any great chronology but, at the same time, have a quaint charm, and are all told in that broad Fermanagh/Cavan brogue.

He tells a poignant story of how when one of his uncles was gunned down at the very end of World War One, his formidable granny, Mary Jane Johnston (née Frazer), knew he was killed as he called out to her in a misty west Cavan dawn.

He also recalls getting the last spin on the train at Enniskillen in 1958, and like many, cannot understand why Ireland got rid of the railways, which were so important for so many decades.

And he has some humorous anecdotes about the smuggling that went on the 1950s right up the end of the 1980s in this famous frontier town, and how the locals used their wits to get around the ever- vigilant Customs men on both sides of the Border.

Harold was also interviewed by Sky TV about his views on the impact of Brexit. Jacob Rees Mogg, the Conservative MP, was also interviewed, and he popped into Harold’s shop for a chat a few years ago.

Harold has also written a very well received article on the Blacklion and Glenfarne Railway Line in a prestigious publication, ‘The Spark’.

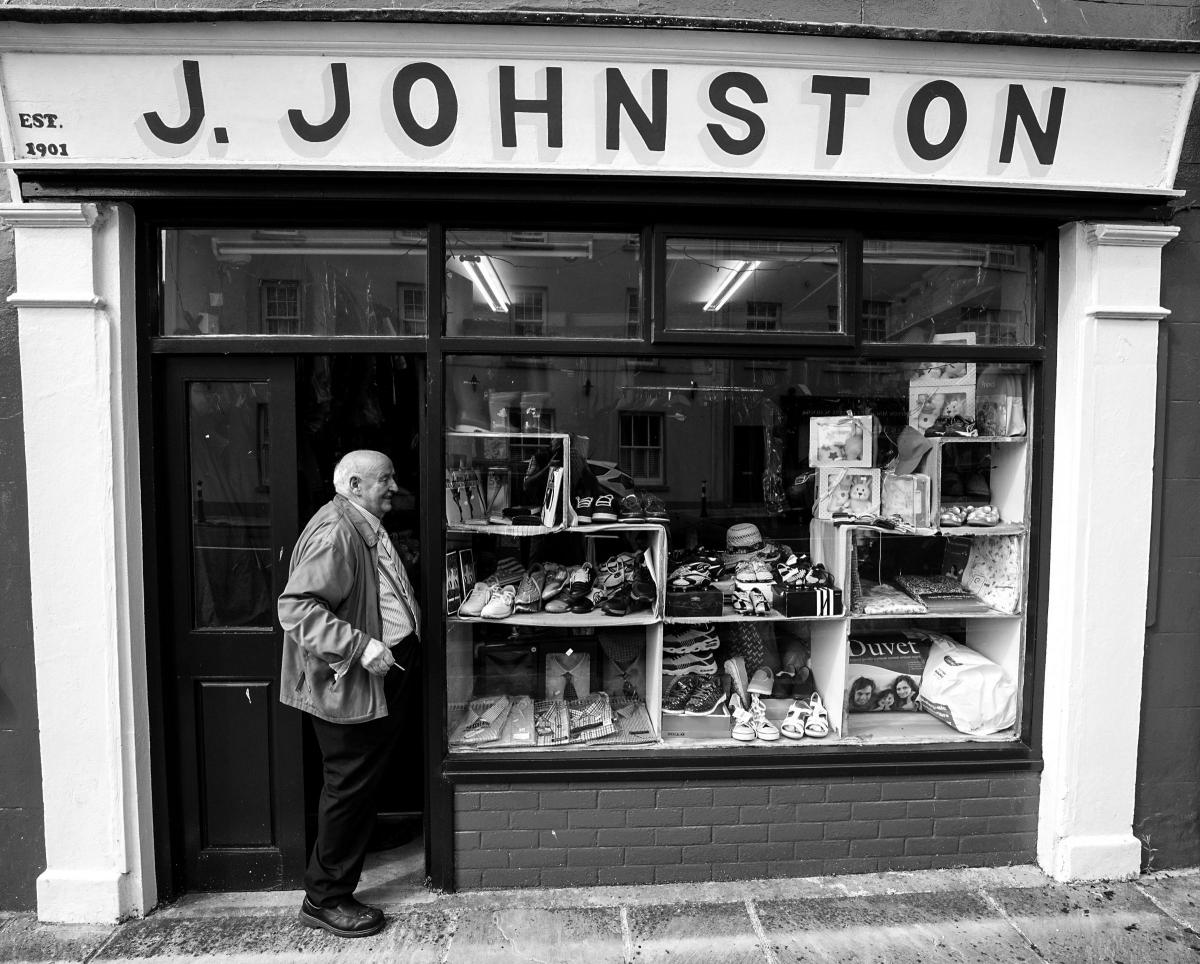

His iconic drapery shop has been on the go since his super energetic grandmother Mary Jane Frazer, who was from Belcoo, opened it in 1901 after marrying his grandfather, Joseph Johnston, who came from Corislea outside Cavan town in 1896.

They married in Killinagh just up the road from a shop where you get the rich smell of real leather shoes and jackets, coats, wellingtons, boots, suits, shirts and ties piled to the roof in no particular order – a treasure trove to be looked at leisurely.

And although Harold has been running this shop since the mid-1960s, he is the most unlikely businessman you will meet, as there is not a materialistic bone in his body.

His granny was a true legend, and a hard-working woman who served her time as a seamstress in Bellaghy, County Derry, and built up a thriving business where she had five seamstresses employed upstairs.

“They made hats, dresses and made a lot of stuff out of red flannel nightdresses, and we still have some of the red flannel in the shop.

“Granny used to do wedding dresses as well, and I remember old women coming in and saying, ‘I got my wedding dress from your granny years ago’.”

The family lived in Belcoo, and Joseph and Mary Jane had five sons – James, Joe, his father, Hamilton and Jack and they were “five hardy boys”.

Harold’s father, William ‘Billy’ Johnston, was a traveller for O’Callaghan’s Leather of Limerick and travelled the country.

Mary Jane’s business was thriving when World War One broke out, as there was a great demand for clothes and sundries, as the shop also sold groceries and other bric-a-brac.

The recruiting sergeant came around to Blacklion and James Johnston – an uncle of Harold’s – joined up when he was only 17.

Sadly, he did not survive the war. He was in the cavalry, and he used to exercise the horses in Belcoo before he joined up.

“It was March, 1918, and there was one big push on, and James was thrown into the front line.

“The trench that they were in was overrun, and he was shot and fell back dead.

“Granny Frazer came down to the shop on the day after, and told the girls: ‘James has been killed in the war.’

“She said, ‘I heard him calling me at dawn this morning’, and I knew it was him, and a white mist came into the room at the time, and it went out the window.

“She went into mourning straight away, and the others were saying, ‘This could not be’, as no word came.

“But granny said she knew he was dead.

“Eventually, a fellow from Letterbreen called Brownlee, who was in the same trench as Uncle James, was taken prisoner in Germany, and he had James’ bits and pieces with him when he was released in 1919, and came up to the shop to granny.

“He told granny that James was calling for her when he was dying, and that was the same day and the same time that she had spoken of.”

Harold had a French film crew in a few years ago asking about a memory of World War One, as so many Irish people were killed in it.

“I told them that story about my uncle, and they told me that same story [has been told] in France. It is always the mother that gets the message, because who is closer to a child than its mother?

“But they had nothing about World War Two.”

Harold’s grandfather, Joseph Johnston, died in 1920 and Harold believes that he never got over the son’s death.

Mary Jane soldiered on for another 26 years, running the shop, and all of her sons were in the army and “she would not have them lying about”.

Harold then relates the well-known tale of when the circus came to town at the start of the Second World War.

“The war broke out in September, 1939, on a Sunday, and they [a passing circus] headed for the neutral Free State as they had some Germans, and they would be lifted if they stayed in the circus.

“It was my brother told me the story, and I am the youngest of eight, and they [the passing circus] came to the Customs on the bridge between Belcoo and Blacklion.

“They had everything – tigers, lions, and all kinds of animals – and they were told they had to give five days’ notice.

“But the circus man said they had to get out of the North because of their Germans [members of the circus], and the Customs man rang his boss, who thought the Customs man was in the horrors of drink and was only imagining it.

“But he wasn’t, and they were let in, but they had to stay in Blacklion. They put on a show where the Enterprise Centre is, and they got a huge crowd because it was sensational, and we had the stilt walkers, who walked up the street and put in circus tickets through the top of windows!”

Harold’s older siblings used to listen to William Joyce, AKA Lord ‘Haw Haw’, who broadcasted propaganda for Adolf Hitler’s war effort. He was later hanged for treason.

“He had news on at 7.30pm, ‘Germany calling, Germany calling’, and this evening he said the British Army were after putting up new defences in Enniskillen, but ‘they have put the defences on the northern side of Enniskillen, but we are going to attack from the south’.

“There was an enquiry and they found out that there was a German spy up on Cuilcagh Mountain, who was feeding ‘Haw Haw’ information, and they could not get him.”

The Second World War, and the six or seven years afterwards, were good days for Blacklion and Johnston’s drapery store.

Rationing went on in Northern Ireland until around 1956, but there was none south of the Border.

“There was plenty of butter and sugar, and we sold some groceries, which brought people in and a lot of people came from Belcoo, and even as far away as Tempo, to come and shop here because Blacklion had things that you could not get in the North.”

Meanwhile, Harold’s mother – Florence Barber from Coolaney in County Sligo – married Joseph Johnston in the 1930s, and she had four sisters and one brother.

All of the Barber girls were schoolteachers and Harold’s mother met his father when she came to teach in the Church of Ireland Primary School in Blacklion.

It appears that Harold took his love of learning from his mother and his aunts.

There was eight in Harold’s family, but only he and a sister are still alive.

Harold was born in 1945, and he was in the shop since he was a child. He segues into a tale of how his sister Dorrie lost her green dress during the war to a dutiful Customs man.

“Dorrie was in the shop and granny gave her a green dress, and it was parcelled up for her birthday, and she was only about five, but the Customs man took the dress off her as she was going across the Border to Belcoo.

“She started to roar and cry, and the RUC were wondering what was wrong, but she never got the dress back.

“She never wore a green dress again!”

However, the locals often hit back at the Customs, using native cunning that has served Border folk for generations.

“There was a woman in Vincey of the Bush’s bar, and she asked him if there was any man who would ride a bike over from Belcoo for her.

“Vincey got a man to do it, and said they would give him a few drinks to pay for it.

“This man went across the bridge – but didn’t the Customs follow him, and they followed him out to Ben McHugh’s Pub in Glenfarne.

“He went into Ben McHugh’s and he stayed there, and eventually the Customs left, and he told the woman that she could pick up her bike there, so that was one time the people got the better of the Customs.

“Smuggling was big in the 1940s and 1950s, but it did not help my father.

“He had land in Blacklion, and he had six bullocks on it, and these boys were smuggling cattle across to the North through his land.

“My father’s cattle followed them, but the police were stopping out on the road, and didn’t they lift his cattle! He never got them back – all the cattle were seized.”

However, the local GAA team did manage to get the better of the Customs.

“There was Gaelic football here, and leather footballs could not be got. It was in the early 1950s, and they heard they could get one in Enniskillen.

“They bought it and it was dear, but when they came back to Belcoo, the Customs man was out on the road. He would have taken it off them.

“So, one lad said to another to go in by the back of the creamery, and he would meet up with him on the Blacklion side.

“The lad went up the railway tracks to the back of the creamery and he gave it a good kick over the Border, and the other fellow caught it.

“You could say that was one instance where the Customs man got the boot!”

On another occasion, a few women were trying to bring butter and sugar across from Belcoo to Blacklion. They saw the Customs man, and they did not want to chance passing him.

“There were a few young lads, and one of my brothers was one of them, and they said to the women that if they gave them sixpence apiece, they would get rid of the Customs man.

“Butter was very cheap in the North at that time, as it was 3 and fourpence in the North, but five shillings in the South.

“The boys had a big bit of cardboard with them under the bridge, and they drew the Customs man’s attention and he, like an eejit, went after them.

“They ran as far as where Clancy’s petrol station is now in Blacklion, and he caught up with them, and asked them what was in the cardboard box?

“When it was opened, there was nothing inside, and in the meantime, the women had sailed across at their ease!”

And then Harold recalls the days when the American Army was stationed in the Big Meadow during the Second World War, and soldiers were camped up the Boho Road.

“My mother remembered giving them daffodils to give to the mess tables to make it feel like home.

“And they went off to the invasion of Normandy in 1944, and they kept up contact.

“My older sister remembers that any girl that had a bicycle would hang on to their jeeps when they were going up to the station for a lift, and they would give them chewing gum and stuff.

“The Yanks also used to check the trains for deserters.

“My sister had no bike, and she was looking at her friends getting an unusual lift, and it was fierce fun and something you would not see now!

“The Americans used to climb up and down the Hanging Rock, and assembled bridges across the Cladagh River, and they also had firing ranges as well.

He added: “Blacklion had a great Northern trade in the early 1950s as the rationing was still on in the North, and they came over for the essential items, and our shop was going well.

“But money got scarce in the late 1950s. It picked up again in the early 1960s when the electricity was being put in, and it gave great employment here, as did Loughan House when it was first built for the White Fathers earlier in the 1950s.”

Harold, born in 1945, says his earliest memories are of the ‘Big Snow’ in 1947 – a two-month period that saw several major blizzards and 10- to 20-foot snowdrifts across much of the island.

Harold went to the Tech in Enniskillen from 1958 to 1962, where John Maxwell was a very young PE teacher. He took over the shop when his father passed away in 1968, and liked history and English.

He remembers another historic moment for the area. “In 1958, they were taking up the [railway] tracks and another lad said to me to go down to the station to see what was left.

“It was in September, and there was a man turning the big engine around on the turntable, and he asked us if we would like to get the last spin out of Enniskillen on the railway.

“We got into the train, and he drove it out, and he brought us to the end of the platform; he had to go to Belfast with the train.

“It was a terrible pity that they got rid of the railways, and people could not see any further than their nose. When the railways closed in this area, it caused serious unemployment.”

The railway came through Belcoo, and Harold remembers being over in Belcoo for the line’s closing-down in 1956 when he was 11.

Harold travelled on the rail car, which was effectively a ‘bus’ put on rails, on a special chassis, and he went to Enniskillen on it in the mid-1950s.

He went into working in the shop first in the mid-1960s, and he “just drifted into it and I have been here ever since”.

Harold has seen huge changes in Blacklion over the years.

“When I was a young lad in the late 1940s and early 50s, there were three shoemakers in the town, and you had a lot of pubs – The Bush, Frank Eddy’s, John McGovern’s Bar, Brian Dolan – who was also an undertaker – Peadar Greene’s on the corner, and Philip Dolan’s, and we had four drapery shops, with Peter Maguire’s, Charlie Dolan’s and McManus’s along with our own.

“There were fierce big fairs in Blacklion, going right back to the 19th Century, and the streets were black with cattle when I was a young lad.

“Blacklion was very central on the main route between Sligo and Enniskillen, and of course we had the railway, which could transport cattle too.

“There were loads of sheep, going since the 1850s.

“Originally, there were Hiring Fairs here – on May 22 and November 19 – when farmers came from down in Tyrone and East Donegal and hired help, and some of them earned enough money to bring them to America.

“They were tough times, and the fairs were still here until 1974, but the new mart in Manorhamilton killed them off.”

As for when such fairs were held: “It was a busy day, and some of the traders had to put up barriers to stop the cattle from damaging anything.

“Way back before that the schools used to close during the hiring fairs as there were too many people in town.

Blacklion had another boom in the 1970s, ironically partly due to The Troubles as the town was flooded with gardai and the Irish Army on Border duties.

“There were 46 gardai here, and six sergeants at a time in the 1970s. They had a 24-hour shift, and they were young men and had money to spend, and the pubs and the shops did well. They were staying in the town.

“I am sure that at least half a dozen of them met their wives at the checkpoint over the years.

“You would be going through the garda checkpoint three or four times a year.

“There were good times in the Black in those days, even though we had The Troubles too.”

“The Troubles had a huge impact on us, and I remember a rocket being fired at Belcoo barracks from the bridge, and the shop was packed, and all the people left. Many of them did not come back.”

Harold also recalls the iconic Glenfarne Ballroom of Romance built by a clever Cavan man, John McGivern, hailed as a dealer in dreams in the 1940s and 1950s.

“It was known as the ‘Ballroom Of No Chance’, and local historian Margaret Gallagher had a great spake about it.

“I was in the History Society with her in Belcoo.

“Somebody once asked her why she never married, but she said she used to go there, and she was looking for a fellow with a car. If you had a car in them days, you were miles ahead [on the dating scene].

“But a lot of other lassies were looking for a lad with a car, and Margaret could not get a fellow with one, saying: ‘I let all of the lads with the bicycles go by’.”

These days, Harold ruefully says that most of the local people have gone from the town.

There are some 180 Ukrainians living in and around Blacklion, which Harold believes to be a good thing, as they are bringing life to the area, and helping to keep up the numbers in the local schools.

“They do not spend much here, as they go to Lidl and Aldi, which is what they were used to in Ukraine.”

He is very proud of his famous neighbour, Neven Maguire, whose famous restaurant is just across the street from Harold’s shop.

“I knew his late father, Joe, and [Neven’s mother] Vera, and it was from Vera that he got his cooking skills.

“Neven is a credit to the village, and I have eaten in his restaurant, and he has a great way with him.

“His restaurant is always booked out now, and there are a lot of big cars there, and he also does B&B.

“I remember the first time Neven got national publicity as he won a competition in France, and I was talking to his late father Joe, who was bringing him away in his Transit van in the 1990s.”

The famous Loughan House is just out the road, and it gave a lot of employment locally when it was built for the White Fathers in 1955, and was subsequently turned into an open prison in 1972.

“Most of those who are working there are living and working in Sligo or Cavan, but we had a few boys from the Anglo Irish Bank were there too.”

And then he tells a great yarn about three inmates who stole a boat and went across the lake and went walking into Belcoo.

They asked if there was a railway station, and when told there was, they asked if they could get a train to Dublin.

“The man said they were a bit late for the Dublin train as the last one left in 1956!”

Just a few years ago, Harold had a chat with Sky News about the effect of Brexit on his area, and Tory MP Jacob Rees Mogg was also interviewed.

He came into the shop, and Harold found him a "very entertaining man and he was sitting there where you are”.

Harold added: “Brexit was a bit of a fraud, and they did not know what they were doing, and there was all sorts of stuff going on. You could never police the Border anyway, as there are so many crossing points.

“People were kind of looking forward, and thought there would be more smuggling,” he chuckles.

He added that one woman who was giving out about Rees Mogg said that he was a typical aristocratic upper-class Church of England Tory.

“I had to tell her that he was well up in her own Roman Catholic church, and she got an ojus gunk.”

Harold laughs a lot during our chat, and he loves laughter and making others laugh.

Being in his company is an enriching experience, and you just know he has so many more great stories to tell, and he remains a gentleman ... and a gentle man.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here