After four visits, I still don’t understand this place, nor have I evidence that it was used during the 1920/21 War of Independence.

Even if I had lived at that time, I would probably have had no knowledge of its existence either.

Yet personal details were left within its dark interior, scratched on a wall furthest from the light at its entrance.

A calling card to the future, perhaps, but the act of leaving them there surely undermined a code of secrecy that required those who used such clandestine places to leave no evidence of having been there.

My first visit was facilitated by Jim Gilleese, who had been in conversation with Frank McManus about a talk I had given in Kinawley about an early lost Christian church below Benaughlin Mountain.

Jim told Frank about a cave on its steep east-facing cliff which contained Latin writing.

Now in his eightieth year, Jim first visited it as a ten-year-old, hunting rabbits, and then again with his young children 40 years ago.

Might there be a connection between the early ecclesiastical church and the cave?

Perhaps a hermit had lived there long before the time when legendary Donn Bin Maguire rode out from beneath the mythic mountain on his white steed.

Two days later, Jim guided me up through thick forestry to a cliff face below the heathery ridge line.

After fighting our way through briars, we scrambled up a steep slope to find the cave, its dark entrance barely discernible behind the undergrowth.

Clearly, no one had ventured up here in a long time. He remained outside while I entered.

Using a headtorch, I walked along a passageway before dropping on my belly to negotiate a short section where the roof lowered to three feet above the floor.

Emerging, I stood upright within a small back chamber. The cave was about 20 metres long, a metre and a half wide, and three metres high.

The low roof in the centre effectively created two chambers. It was empty, except for a few animal bones scattered on the floor.

Failing to find writing, I rejoined Jim. Looking across to Kinawley and Swanlinbar under Molly and Slieve Rushin mountains, he reflected how on his last visit, he had seen ground disturbance on the heather plateau above the cave, and wondered, given its vantage point overlooking the Mullan Border post below, if it had been used during The Troubles.

My second visit was with Alma McManus, who crept under the low roof to the back chamber and found what I had missed on my visit with Jim.

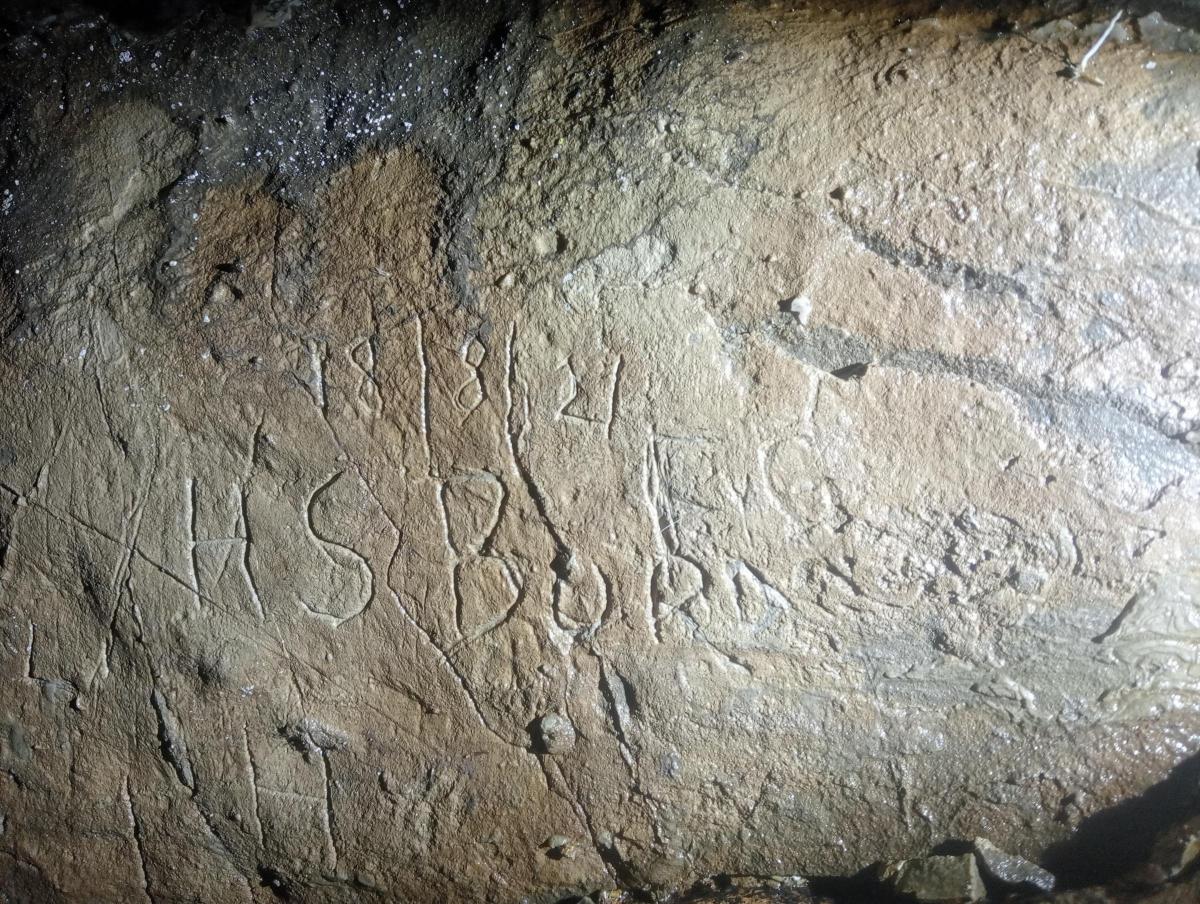

I joined her to see, highlighted by torchlight, five sets of initials, a surname and 18/8/21 scratched on soft calcite rock.

Did the date refer to 2021, or 1921? With no evidence of a beaten pathway through the undergrowth to the cave, it seemed likely that the inscriptions and date must refer to 1921.

But surely others knew about the cave? I checked with Tim Fogg from Fermanagh Caving Club, who confirmed that it was known to its members as Pollabrock Cave, but when located many years ago, it wasn’t surveyed.

Reporting later to Jim about the discovery of the initials and date, he indicated that he was unaware of them, as he had never ventured to the back of the cave; his remembered Latin script was at the entrance.

The third visit was with caver and geologist John Kelly, who described Pollabrock as a fissure within Dartry Limestone rock, that the initials had been scratched on soft calcite or moon milk, and modifications had been made to the wall of the cave at head height to remove obstructions.

My final visit was unaccompanied, and it revealed another inscription close to the original grouping, which seemed to signify a military officer’s rank.

I turned to the Defence Forces Pension Records Archive in Dublin to crosscheck names of combatants in the Fermanagh and Cavan brigades of the IRA with the initials found on the wall.

Contemporary reports from active units at the time showed that this was a febrile and dangerous period.

Throughout 1920-21, local police barracks were burned in Letterbreen, Arney and Trillick, and the Enniskillen Income Tax Office was burned.

Derrylin Courthouse and Barracks were also burned, Belleek Barracks was captured, and raids for arms were a nightly occurrence.

In nearby West Cavan, there were raids for weapons and attacks on barracks in Swanlinbar, Bawnboy and Ballyconnell.

Intelligence and secrecy were clearly paramount in this guerilla war.

To avoid detection, combatants may have moved easily enough through the wild trackless Cuilcagh uplands between Leitrim, West Cavan, Sligo and Fermanagh.

Pension records note that a hiding place for a flying column in the mountains was established outside Belcoo to give anyone “wanted because of his activities a definite place to go to”.

But then, between May and June, 1921, a cavalry column consisting of three regiments, supported by the RIC, auxiliaries and military aeroplanes, mounted a search through counties Longford, Leitrim, Cavan and Monaghan.

When 700 men were arrested in nearby Leitrim, poorly-armed guerrillas in the wider area presumably went to ground.

Pollabrock cave might then have been used as a hideout, as was Tormore cave high above Glencar in County Sligo during the later Civil War in 1922, when 34 IRA men on the run from Pro-Treaty forces hid there for five weeks before surrendering.

Geologist Kelly, who contributed to the archaeological report on Tormore’s excavation, noted that Pollabrock cave was similar in size to Glencar, and could have accommodated a similar number of men if needed.

A truce was finally called on July 11, 1921, five weeks before the August date inscribed in the cave.

Fear and suspicion lingered, however, and combatants were reluctant to return to normal life, although once assured that peace had finally broken out, they may have felt confident enough to break their rule of anonymity and left their calling cards at the back of the cave.

So what do we know about Pollabrock? My bet is that the cave was used as a hideout.

Research of pension records revealed that two sets of initials on the wall matched the initials of two names on brigade lists.

Of itself this is not sufficient, but absence of evidence is not necessarily evidence of absence.

So, rather than scratching in the dark, it is perhaps best that the cave keeps its secrets, and I resume my search for the hermit and Latin script.

In order of appearance, thanks to Frank McManus, Jim Gilleese, Patrick Gabriel McManus, Francis O’Reilly, Packie Drumm, Eddie Brogan, Alma McManus, Roisin Smyth, Marion Maxwell, Tim Fogg, Pam Fogg, Johann Farrelly (Cavan County Museum), John Kelly, Iona McGoldrick and Arlene Anderson.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here