The death of 19-year-old army lieutenant Jack Carrothers 100 years ago during the Battle of Passchendaele still leaves its mark on his nephew Sam, who hopes a published book of Jack’s letters will continue to “make people aware of the evils of war.”

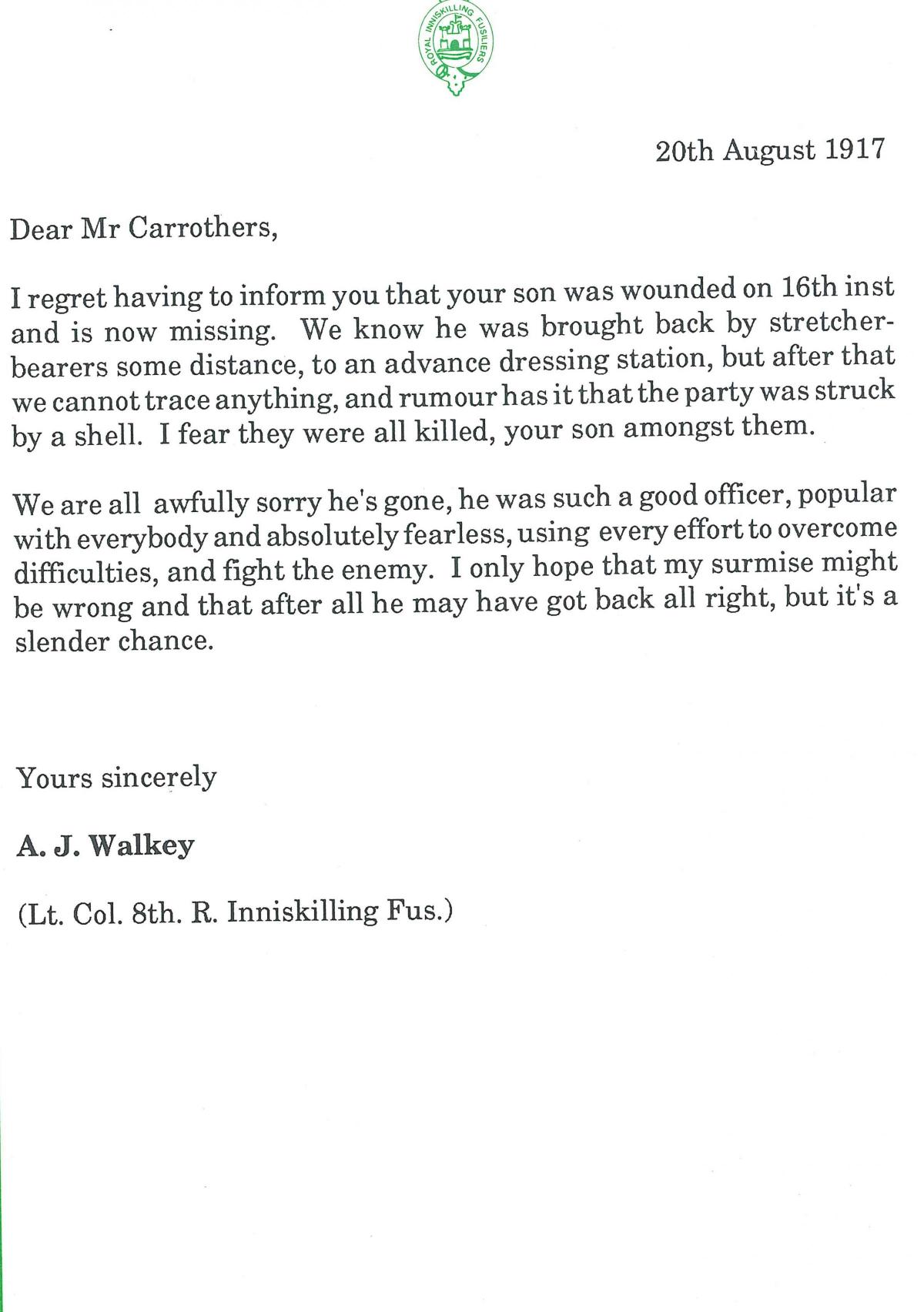

John Samuel Carrothers was born at Farnaught outside Lisbellaw. He attended Portora Royal School and worked for the Irish Land Commission before joining the Officers Training Corps in December 1915. After extensive training, he received his Commission on December 19 as a 2nd Lieutenant with the 3rd Battalion Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers and was to became one of the doomed generation of young men who gave their lives during the First World War. He was killed on August 16, 1917 at Langemarck as he was being stretchered to a dressing station and his party was directly hit by German shelling.

“On the one hundredth anniversary of Jack’s death, I want to make people aware of this book of letters and to help make people aware of the evils of war,” said Sam Carrothers, a son of Jack’s oldest brother.

“I went to the World War One battlefields a few years ago and even thinking about it now, I feel emotional about it,” commented Sam, who still lives at the Farnaught homestead.

Jack was one of seven young men from the Lisbellaw area who fought in the First World War and Sam is in the process of planning a special Harvest of Thanksgiving to mark Jack’s death and to give thanks for those who returned.

A steady stream of letters were sent by Jack to his mother and sister, dated from January 11, 1915 – August 13, 1917. Sam found these letters locked in his father’s desk and opened a museum at the family home. Many visitors urged him to publish Jack’s letters from the front, which he did in 1992 when he collated ‘Memoirs of A Young Lieutenant’ in memory of his uncle.

The letters begin at the start of Jack’s Army life and depict how he was looking forward to getting home to see his mother in April 1916 but was forced to seek refuge in the Military Barracks in Dublin because of the outbreak of the 1916 Easter Rising. He does not spare detail, writing in unflinching terms about an incident on Thursday, April 28: “Two snipers appeared at a chimney quite close and we opened rapid fire on them, the chimney fell and also both the snipers. One was only wounded and he was brought in as a prisoner. His coat was covered with the blood and brains of the other sniper. A sight like this soon puts the notion of war out of one’s head.”

Later in the same letter he wrote: “I have seen enough of the horrors of war without going to France to see any more.”

There are regular light-hearted entries, queries about the farm such as: “Are the apples ripe yet?” or “What price did the men get for the pigs?”

On February 23, 1917 he writes of his “sudden orders for France” and said: “We will be well tired when we land in France. We stand all the way over with life-belts on.”

And there are regular requests for socks. “It makes no difference how heavy the socks are, so long as there are no lumps in the soles,” Jack wrote. From the trenches, he wrote: “Send socks. They are the most useful thing out here that I know of and they soon wear out. The men get a clean pair of socks every morning. This is the only way we can counteract trench feet.”

On May 4 he wrote that he heard the cuckoo on May 1 and added: “Nightingales sing ceaselessly in No Man’s Land every night, so we get plenty of good music.”

On August 7 he wrote to his sister saying: “I am writing this under strange circumstances as I am sitting in a German dug-out about five miles directly in from of Ypres. Shells are roaring over (going both ways) by the dozen. I am the only officer of this Coy. In the front line and I am absolutely isolated as no one can move a finger during day light without being sniped. My men are well dug in but are up to the knees in mud. The weather is good now so it’s not so bad.”

Jack’s last known letter was to his mother on August 13 and contained nothing of note. Jack wrote: “I have no special news as I have written so often. The weather is inclining to be wet again.”

A letter to Jack’s sister on September 6 from Captain A. H. Robbins outlines his extensive search for Jack.

It states: “I am very much afraid that we will never see him again and you have no idea how I miss him. He was ... our best officer ... and all of us who are left miss him more than we can say. He was a great pal and a great help to us through these times.”

As he reflects on 100 years since Jack’s death, Sam would love to be able to visit his uncle’s grave.

He laments that Jack “probably sank into the mud of Passchendaele.”

A tablet in memorial to Jack Carrothers is placed inside Lisbellaw Presbyterian Church.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here