To the west, we enjoyed a panoramic view of Cuilcagh, Benaughlin and the Iron Mountains.

The villages of Bawnboy and Swanlinbar were hidden below by the fall of the land.

At 1,300 feet high, the surrounding moorland landscape, with its winter colour palette of burnt umber and rusts, did not appear at first to be a likely place to find the abandoned millstone quarry we were looking for.

No soaring cliffs of stone, rusting machinery nor screeches of peregrine falcons here.

Yet the map showed it to be among nearby sandstone outcrops which surfaced through the bog as low rounded hummocks on a curving slope just below the summit of Slieve Rushen on the Fermanagh/Cavan border.

The terrain became difficult, and local geologist John Kelly and I took care not to fall between deep tell-tale gaps among the now distinguishable heather-covered sandstone bedrock.

And then, unexpectedly, we stumbled upon the unmistakeable outline of a millstone partially hidden by nearly 150 years of regrowth within a hollow of worked stone.

Lying on its side, it was over a metre and a half wide, and 30 cm deep.

A small section had broken off and had presumably been rejected, its makers moving on to start another.

Next to it was a small, roofless, circular stone shelter with partially collapsed walls; a reminder that this mountain linear quarry was once a workplace where men toiled to extract and shape millstones for an earlier industrial age powered by water and coal.

The soft swishing and mechanical thrumming of nearby windmills reminded us that this landscape was now used to harness wind energy to power our emerging post-carbon age.

But what had brought us to search for millstones at this high and lonely place?

While assisting Killesher Community Development Association to repair the water wheel at Tully Mill, I wondered where their millstones had been made, and then I remembered having seen a sandstone quarry on a heritage map a year ago.

Rechecking, I found it again in the townland of Mullaghlea (grey hilltop), just below the summit of Slieve Rushen.

Its Irish meaning chimed nicely with the maps’ accompanying site-note which stated that the quarry was located on a bedrock of weathered grey orthoquartzite sandstone.

This hard-wearing rock was ideally suited for the relentless grinding motion and pressures generated by the milling process.

Dating from around 1750 to the 1920s, vertical water wheels in Ireland were used to power different types of mills to produce flour, linen, wool, and timber.

There were around 2,500 in Ulster, with 157 in Fermanagh.

Used in pairs, the average millstone for corn was 1.6m in diameter and weighed over a ton.

The centre hole was known as the “eye’”, and it was where grain entered the millstones to be ground into flour.

The base stone remained stationary, while the top runner stone created a grinding action between the two.

A complex pattern of scissored grooves cut into the stones pushed the flour out towards their outer edges, from where it could be channelled and bagged.

Standing at the quarry we wondered who made this mountain millstone, and how they moved it down the mountainside.

The Mullaghlea quarry was probably worked on a seasonal basis by local farmers.

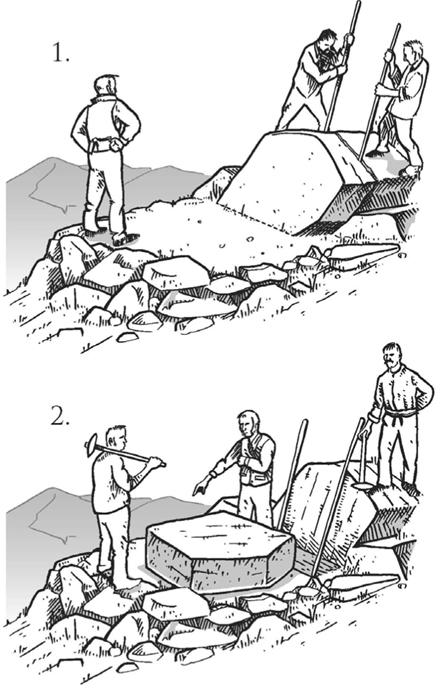

Working to order, they hand-drilled holes in the exposed sandstone, inserted metal plates and drove wedges in to split them.

According to the Ordnance Survey Memoirs of the 1830s about the Lough Eske quarry in Donegal, two stonemasons produced one a week.

Transporting them from remote locations was an impressive feat.

In the English Peak District, where the stones were finished, a wooden axle was inserted through the central eye of an upright stone and four men – two on each side – rolled it down the hillside from where it could be pulled by wagons to local mills.

Further visits to Slieve Rushin revealed three more unfinished stones, one large and two small (possibly grindstones to sharpen tools), which suggested that they were transported by horse and slype (sledge) to be dressed and ‘eyed’ below the quarry near a roadside.

Assuming this was the case, it entailed sliding the heavy millstones horizontally on to the slype, which was then dragged by a horse harnessed at the front to pull it, and another at the back to act as a brake, down a long straight lane to the valley floor through the extensive system of enclosed chequer-board fields and latticed laneways of Corneen townland, before being dressed and transferred onto a heavy cart for delivery.

Around 1890, the industry rapidly came to an end as flour was milled by modern steel rollers, and the half-finished millstones were simply abandoned where they lay.

Although we do not know the names of those who laboured at the small open quarry site with its scattered stones high on the western slopes of Slieve Rushin, the site is as inspiring as any ancient mountain-top tomb site I have seen, and remains as a testimony to their knowledge and skills, and the dignity of labour.

But was this quarry the source of the millstones at Tully Mill?

To determine this, John Kelly took a small rock from the site, and along with other small pieces chipped from stones at the mill and elsewhere, he will compare them chemically through laboratory analysis.

If they match, we will know at least that this was also an important and connected place, and part of a supply chain which provided essential components for a bygone industrial age.

Notes: A molinologist (from Latin: molīna, mill; and Greek λόγος, study) is one who studies mills and other similar devices which use energy for mechanical purposes. I fear that the process of undertaking research for this article may have turned me into one.

Thanks to: Killesher Community Development Association, Geologist Dr John Kelly, Sebastian Graham, Mills and Millers of Ireland, Alma McManus, Jimmy MacKiernan, Margaret MacKiernan, Sile McKernan, Seamus McHugh and Ciaran Maguire.

This article is also available on Barneys blog, https://notes-from-the-field.blog.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here